Vishakha N. Desai, Vasif Kortun, and Hamed Yousefi in Conversation with Lynn Gumpert

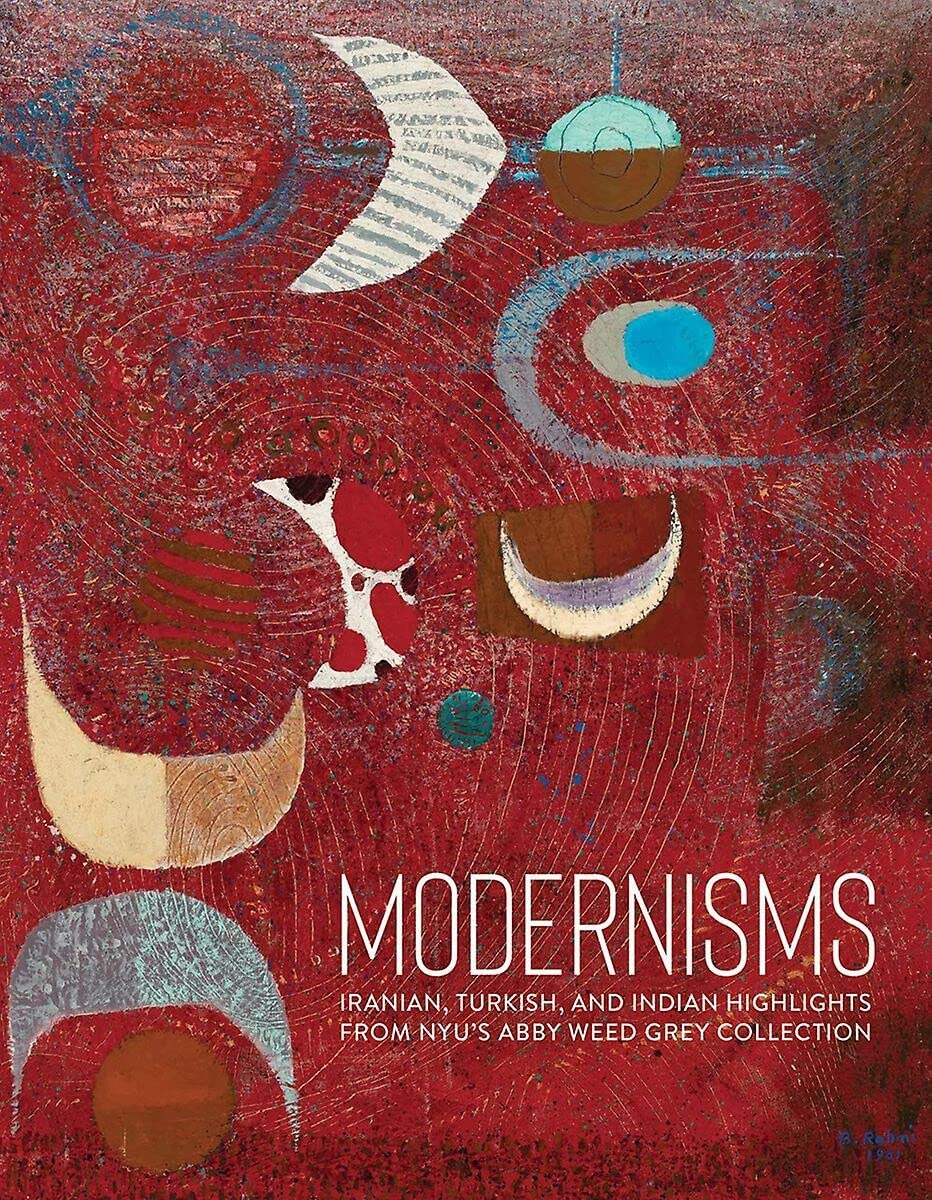

Modernisms: Iranian, Turkish, and Indian Highlights from NYU’s Abby Weed Grey Collection, Catalog, 2019

Lynn Gumpert: The Grey Art Gallery, the fine-arts museum of New York University, has the largest institutional holdings of modern Iranian art outside Iran; the largest collection, as far as we know, of modern Turkish art outside Turkey; and some eighty works of modern Indian art. Mrs. Grey embarked on her mission to collect contemporary art by non-Western artists in 1960. She had led, up to that point, a fairly conventional life as the wife of an army officer. When her husband, Lieutenant Colonel Benjamin Edwards Grey, died in 1956, she was only fifty-four years old. She found herself with a sizable fortune, and she thought long and hard about what to do with it. We’re still uncovering her motivations, but we know that she joined fourteen other women—mostly New Yorkers—on a two-and-a-half-month trip around the world. In March 1960 the group landed in Tokyo, where she bought some Japanese prints, and then traveled on to Thailand, Cambodia, India, Nepal, Pakistan, Iran, and Israel. Searching for contemporary artists who were breaking with the past, Mrs. Grey was thrilled by the art she saw in Iran at the Second Tehran Biennial. She returned to Iran seven more times, to India three more times, and made four trips to Turkey. I thought that we would start by talking briefly about the political situations in those three ountries in the 1960s in order to provide a broader context for the works of art she collected.

Vishakha Desai: In regards to India, it is important to recognize that the early 1960s were very different from the later 1960s. India had gained independence only in 1947 and, in the early 1960s [Jawaharlal] Nehru was still alive. It was also the height of the Non-Aligned Movement. Nehru died in 1964 and, after much struggle, his daughter, Indira Gandhi, entered the scene. Thus nationalism and anticolonialism were very much a part of the ethos in the first half of the decade. At the same time, India was struggling to figure out how to maneuver economically. Major Indian Institutes of Technology (I.I.T.s) were being developed. Some were looking at Fabian socialism, others were looking to Russia to understand the role of the state in making a modern nation. Also in play was the Nehruvian ideology of a modern nation; Le Corbusier was invited to build Chandigarh for the new capital of Punjab, and modernism became equated with this new nationalism. By 1967–68, the situation was very different. Mrs. Gandhi turned very anti-American, and everything American was kicked out of India, including NGOs and the Fulbright program as well as AFS [originally known at the American Field Service], a high-school exchange program that I was on from 1966 to 1967. A certain privileging of a Western modernist ethos occurred early on, when the situation was still very open, but I think we should look at the reasons why the art Mrs. Grey collected is so ecumenical. As Ranjit Hoskote notes in his essay reprinted here, different schools and “isms” were not completely defined in the 1960s, so Mrs. Grey was exposed to a wide gamut of what was being produced. The privileging of one part over the other part of the Indian art establishment didn’t occur until much later. Modernized cosmopolitan culture is what she encountered rather than much more diverse vernacular traditions, which she would not have had access to.

Vasif Kortun: I am curious about the situation between India and Turkey, and also between Iran and Turkey in the 1960s. Turkey participated in the first Non-Aligned conference, in 1955, in Bandung, Indonesia. Turkey’s Minister of Foreign Affairs made a very pro-NATO and pro-America speech, after which he was shunned by Nehru. There was a real wedge for many years between Turkey and India. During the conflicts between the Greek and Turkish Cypriot communities, India sided with the Greek community. Looking at the relationship between the three countries more broadly, Turkey occupied a unique position. The country was built on the remains of an empire, which it had embraced thoroughly. As such, Turkey had no experience of the education of the colonized and could not see itself at that table!

VD: No subaltern, there.

VK: Correct. Turkey also set its identity formation vis-á-vis the West. But its relationship to Iran at the time is another story. The two countries share a border that neither has contested for more than four hundred years—and they also share the Kurdish problem. Iran was regarded very positively in the 1960s; both countries belonged to CENTO (Central Treaty Organization). Turkey and Iran, along with Pakistan, formed a geographic belt that prevented the Soviets from expanding south. Incidentally, there was a Turkish art exhibition that took place in Iran and Pakistan in 1961, supported in part by CENTO. Iran and Turkey were also the only non-Arab countries in that part of the world. Turkey’s nemesis in the 1960s—the leftists being dominant—was the United States. Turkey didn’t learn anything from Arab nationalist and African liberation movements or from India. And, in the mid-1960s, anti-American protests begin.

LG: Yes, Turkey was not alone.

VK: The anti-American sentiment was not only about the Vietnam War. As the rightist nationalists would say, “We dislike the Americans but we hate the Russians.”

VD: In other words, there was a gradation.

VK: Yes. And a common sentiment between the left and the right was triggered by the Cyprus situation, which reached a critical point in 1964, when the U.N. passed a resolution to form a peacekeeping force. President Johnson sent a harsh letter to Turkey, stating, “If you continue to fight in Cyprus, you’re on your own. We can’t protect you against NATO, and you cannot use any American arms.”

LG: The situation in Iran in the 1960s was also very complex.

Hamed Yousefi: Yes, Iran can be located, geographically and—in terms of the debate about nationalism and Cold War politics—between India and Turkey. In 1951, Mohammad Mossadegh, the nationalist leader, announced a policy of “negative equilibrium,” which is later transitioned into the Non-Aligned Movement. But for Mossadegh, the binary was not the U.S.S.R. and the United States, but the U.S.S.R. and the British Empire. Mossadegh was still quite optimistic about the United States, because this was the period when the U.S. was seen as technologically advanced yet historically having emerged from an early anticolonial revolution. What changed this perception was a tragic turn of events, one that changed the course of history and defined the stage on which Abby Grey emerges as an art patron. In 1953, an Anglo-American coup overthrew Mossadegh, disillusioning parts of the Iranian intelligentsia. After the coup, and born from this disillusionment, a new vision of modernity and modernist creativity emerged. And yet, we see a widening gap between the disillusioned intelligentsia and the ruling royal family, because the government that was put in place by the coup remained America’s strongest ally in the region until the 1979 “Islamic” Revolution. So, while Mrs. Gandhi was expressing anti-American sentiments, and Turkey was ambivalent about the United States and the Soviet Union, Iran was viewed as a stronghold against Communism. Despite internal discord, President Carter could still famously refer to Iran as “an island of stability” in late December 1977.

VD: So much for that.

HY: Yes, demonstrations against the shah had already begun in October 1977. But in the 1950s and 1960s American cultural institutions had been very active in Iran. What is fascinating is that the birth of modern art in Iran coincided with the Anglo-American coup—we didn’t have a strong modernist movement in the visual arts before 1953. Nothing like the Bengal School in India, or like in Turkey, where there was a lot of exposure to European modes of perceptual representation. Iranian artists did not create something “original” in the modernist sense until the late 1950s or early 1960s. So, Iranian modernism was, from its inception, completely intertwined with the politics of Iran’s relationship with the United States, which coincided with the cultural politics of the Cold War. It was in this context that Mrs. Grey went to Iran for the first time. And she collected more or less whatever artists were making at the time, the majority of which was later accepted as a “school” of Iranian modernism named Saqqakhaneh.

There was also another lineage that is important for our understanding of the relationship between modernism, national identity, and the politics of the Cold War in Iran. Since the Enlightenment, a group of European intellectuals had been fascinated by the roots of their Aryan origins. Many traveled to India in the pursuit of such roots. It’s too simplistic to label them all as Nazis, but the fact that Iran was understood to be a Muslim country but non-Arab—as was Turkey and, to some extent, Egypt—led to this Orientalist fantasy that manifested itself in a fascination with Iranian, Egyptian, and Turkish arts and culture. In this process, a mode of scholarship emerged based on the assumption that “Islamic culture” is produced in these countries not because of Islam, but despite Islam, insofar as these are countries with strong and rich pre-Islamic histories. Moving forward, when the discourse of Iranian nationalism emerged in the late nineteenth and early twentieth centuries, it was partly influenced by this European trajectory of thought, and many nationalist intellectuals defined the national identity through a return to pre-Islamic heritage. The impact of this intellectual interaction between Orientalism and Iranian nationalism is traceable in the formation of modernism in the visual arts in Iran in the post-coup years. This is because Iranian modernism was closely bound up with the discourse of Iranian nationalism, and Abby Grey’s collection reveals the transnational dimension that is innate in this formation. What is significant in understanding Iranian modernism and its developments after the coup is that the anticolonial side that we see, for instance, in Indian nationalism—a tendency which also existed in Iran in the first half of the twentieth century, before the 1953 coup—was replaced with a nationalism that was inseparable from being an ally of the capitalist block during the Cold War. The post-coup nationalism operated through an advocacy of Iranian identity rather than self-rule. And it was artists who evince this identity-based nationalism, with its lack of anticolonial politics, which Mrs. Grey collects. It also facilitated American institutional support for Saqqakhaneh, alongside the royal court’s patronage.

VD: That’s a really important point. Because of India’s colonial history and its search for national identity, there was a distinction between the political and the cultural, whereas in Iran, they seemed to have come together. In India, the Non-Aligned Movement and the leftists—a lot of the Progressives were very leftist, and anti-American—didn’t completely reject the visual language that came out the West. Both Mrs. Gandhi and many of the intelligentsia shared pro-Russian attitudes. At the same time, the intelligentsia didn’t completely give up on Western aspects of their lives, which came from their colonial legacy. But like in Turkey with the Cyprus situation, Mrs. Gandhi turned anti-American in 1964 over the war with Pakistan.

VK: Exactly.

VD: And this anti-American response occurred earlier in India than in Turkey. The American government’s reaction to the independence struggle also disappointed Nehru. Roosevelt indicated that he supported this struggle and tried to convince Churchill that a solution could be found, comparing the American Revolution to an Indian revolution. Nehru then met with Truman, and asked for support, but Truman did not treat him well. There was a real sense of disillusionment. But that didn’t seem to affect the cultural milieu. Another important factor is that in 1965 the law changed, making it possible for Indians to immigrate to the United States. So, culturally, there was a lot of sympathy for America; politically, it was completely antithetical. There was this distinction between the cultural milieu and the political reality, partly because the government didn’t control the cultural discourse the way it did in Iran, or to some extent even in Turkey, right?

VK: No, the Turkish situation was not far from that of India’s. I’m curious, Hamed, were visual artists members or sympathizers of the Tudeh Party, the Iranian Communist party?

HY: That’s a fascinating question. In the 1940s, the “who’s who” of Iranian culture were in one way or another affiliated with the Tudeh Party. But, as far as I know, there was not a single member of the Tudeh Party among modernist painters and sculptors. The exception here may have been Siah Armajani, who was quite active politically as a young man in Tehran in the 1950s but who was soon sent by his family to the United States to live with his uncle, Yahya Armajani, a professor of philosophy at Macalester College in St. Paul, Minnesota, where Mrs. Grey also lived. I can’t proffer concrete evidence, but it is worth asking if Mrs. Grey’s interest in the East had anything to do with the presence of Yahya in the same town. He seemed to have been quite a charismatic man. Mrs. Grey’s diary entries about her first trip to Iran include references to Siah Armajani and how he might be of logistical help.

VD: Vasif, in Turkey did artists take part in the political struggles at the time?

VK: In broad terms, almost all of them were leftists. But that did not necessarily translate into political activism. There was a concrete change toward the political in the mid-1960s; one can follow it in cinema from 1964, where scenes of dreamy and docile village life shot in the forests of Istanbul were replaced by an unmitigated realism of peasant hardship in films made in Anatolia. The notion of a national cinema was debated against the idea of European cinema. You also see the change in poetry and literature, with the left political sphere expanding and fracturing at the same time. Visual arts lagged behind as artists still argued about the local and international, a discussion congenital to many other countries that struggled between cosmopolitan modernity as a universal idiom and a search for an authentic proposal within it. This effort ended up in forms of local contenting or, to borrow a term from Turkey’s industry of the time, making “montages.” The boycott of 1969 at the Academy of Fine Arts seems like an effort to move beyond this binary constraint.

HY: So, the so-called “local content” of the work is mostly abstract?

VK: Not entirely. But abstraction looked like an easier way to claim authenticity with references to patterning, calligraphy, and heritage extraction. There was still a division: on one side were the abstractionists, and on the other were the realists. Yet they were both of the same paradigm, both had all the circuitous ways of searching for an anchor that could confirm the originality of the work both in terms of its origin and its progressive character.

VD: Are you saying that it is difficult to define local when the region is different?

VK: I’m more curious about what it means to be a modern Western artist in Turkey. The novelist Orhan Pamuk has described this curious condition. Let me read something he wrote about fifteen years ago: “The Westernizer is embarrassed because he is not a European. He is embarrassed for what he does in order to become European. He is embarrassed because the project may not be complete—the project of Europeanization. He is embarrassed of having an identity, and of not having one. He gets angry from time to time of accepting or denying that he is embarrassed. He is angry when people mention that he is embarrassed. He is ashamed to lose his identity because he will be a European.” It is a performance in front of an audience that is not there; a ghost audience. There is no way out of this conundrum once you invest in it.

VD: Yes. And this relates to something I’m constantly thinking about: a dialectical position. Are you modern or are you not? In India, there doesn’t seem to be this dialectic partly because of colonization, and partly because the leaders involved in the struggle all came of age through their Western education, such as Gandhi or Nehru. It was accepted that you are a part of the world and you are seeking your national identity within that world. (This, of course, doesn’t apply to the right-wing Hindus and ultraconservative Muslims who are trying to define what’s national in a much narrower way.) But the very ethos of the nationalist struggle was a certain level of acceptance of being part of the modern world. For example, when Gandhi adopted Indian clothing such as the dhoti, he could appropriate a national image without having to give up his Western, modern traits and tendencies. It would be useful for us to unpack a little bit more the relationship in the three countries between Westernizer or Westernized, nationalist and modernist. All three countries were struggling with this in some way.

VK: In each instance, there was a different description of the “West.”

VD: Exactly. For India, initially it was very Anglo-focused, but gradually it became more Euro-American oriented. For example, [B. R.] Ambedkar went to Columbia for his PhD and then created the Indian constitution, which is much closer to the American constitution than it is to the British constitution. But, at the same time, modern and Western seem to be co-equal in many places—that modern does mean, to some extent, the West.

HY: This dialectic in India seems manifest in the conflict between Nehru and Gandhi. After all, Gandhi maintained a deep suspicion of what he referred to as “modern civilization.”

VD: So you think Gandhi distinguished between modern and Western?

HY: Maybe. We know that he didn’t believe in the modern or bourgeois category of individual consent, which makes him a problematic figure. But what is fascinating is that Gandhi’s interest in nationalism emerged while he was in South Africa—while he was in a minority position in another British colony. So the formation of nationalism in his work was already implicated in the dialectic of minority and majority, or outside and inside, whereas in countries like Iran or Turkey, nationalist movements were mostly articulated by the intelligentsia when they returned to their respective countries and assumed majoritarian positions.

VD: But mind you, most Indian activists were also trained abroad.

HY: Yes, this is probably universal. But the relationship among the three types that Vasif brought up—that is, Westernizer, nationalist, and modernist—is more complicated because it poses questions about a theoretical universal and a historically determined particular. We can say that the universal is defined by the global tendency of capitalism, the particular is the differentiated experience of capitalist modernity at the local level, and modernism is the cultural expression of the experience of capitalist modernity. Attempts by non-Western artists to share this universal experience are what give us particular national modernisms. Nationalism likewise defines itself as differentiated, but universally so, such that everyone wants to claim their own nationalism. The challenge of determining who wants to be a Westernizer and who is a modernizer—which is to say, who tries to insert something of their own into a universal language as opposed to who submits uncritically—may be more complicated than it appears. In general, I would say that in Iran there was a period of optimism and a period of pessimism with regard to the possibility of successfully negotiating between the universal and the particular, between capitalist modernity and the local experience of it. World War II and the 1953 coup marked a rupture there. The most significant intellectual expression of the post-coup loss of optimism is Jalal Al-e Ahmad’s influential essay “Westoxification,” published in 1962. It is translated into English as “Occidentosis: A Plague from the West.”

VK: Ah, gharbzadegi.

HY: Yes, gharbzadegi, or “westoxification.” In terms of modernism—and I use modernism, for the sake of argument here, specifically to talk about visual arts—I’d point out again that Iran didn’t have a modernism before the post-WWII period, .i.e., before the period marked by the discourse of westoxification among the intelligentsia.

VD: In India, I think that agency was important for Indian artists, especially if I speak from the Nehruvian perspective. Early modernism in India was not the same as Picasso looking at African sculpture, or Van Gogh looking to Japanese prints for new forms, new ideas. It arose out of an Indian context—there was a certain agency and consciousness. The Progressives wanted to create new art for a new nation. They were, in a way, consciously saying, “If I’m looking to other places, it is because this is important for my country.” Artists in the Tagore School believed that, for a new world and for a new way, we need to look at this and create that revolution. So that idea of a revolution in an artistic approach with intention. Mind you, ten years later the Progressives fell apart. But it’s also true what you were saying, Hamed, that this was neither new or unique. In India, art was central to the discussion of how to create a new identity.

HY: And you think that this was linked to Nehru’s tendency for modernization?

VD: Absolutely. I think this is why the Tagore School eventually became affiliated with a non-Nehruvian vision of India. Not so much Gandhian, but non-Nehruvian, because Tagore would have never thought of himself as Gandhian in completely the same way. This is why science and technology become so essential. Western science and technology provided an impetus to take part in the new world. That’s why it was important to recognize the agency of artists and of intellectuals. It was appropriation with intent.

LG: Let’s talk about what Abby Grey encountered in the artistic scenes when she traveled to Iran, Turkey, and India. It’s interesting that she chose to go back to these three countries multiple times, but not to other countries. For example, what did Mrs. Grey encounter when she arrived in Tehran in 1960?

HY: Mrs. Grey arrived in Tehran on the last day of the Second Tehran Biennial. She visited the biennial, and this is quite important because it was in this biennial that early Saqqakhaneh works were displayed. She saw an art that not only appeared to correspond with so-defined modern standards from the West, but that was also “spiritual” in its iconography and therefore also “Eastern.” It wasn’t Western in terms of content, as Vasif was discussing in the case of Turkey. Mrs. Grey was also fascinated by how modern the country seemed. Compare this to the description in her notes of a studio visit with Turkish artist Bedri Rahmi Eyüboğlu and his wife, Eren Eyüboğlu. Grey dislikes what she suggests is the bohemian outlook of their studio, but the way she describes this bohemian outlook emphasizes that it is “too Oriental” and therefore not European, whereas we know that bohemian tendencies were central to Parisian modernism.

VD: But maybe she doesn’t know that.

HY: Yes. There’s nothing “Oriental” about a modernist artist who has stuff all over the place. This conflation of the Oriental and what is bohemian is quite interesting. Mrs. Grey was keen to find an Oriental dimension in what she saw, and she also distinguished between what is Oriental in a good way—that is, “spiritual”—and that which she found “badly” Oriental, like the disorganized studio. It is underscored by the fact that in Iran Mrs. Grey was so amenable to work with the royal court. Those people, for her, were adequately Oriental. Farah Diba, the queen of Iran, was an architect by training who had studied in Paris and was very interested in supporting the arts. She appointed her cousin, Kamran Diba, who is also an architect, as director of the newly constructed Tehran Museum of Contemporary Art, which he also designed. The shah’s brother-in-law was the Minister of Culture. So, the political and cultural elites were very clearly organized in a form that suited Mrs. Grey, corresponding as it did to Western institutional models. The Persian institution of monarchy meets European bourgeois nepotism.

VD: So you could call Iran at the time a cultural monarchy, right?

HY: Exactly. Everything happened very quickly and expediently. To an American philanthropist, it would have been very clear with whom you should talk and work. Another important factor was the Iran–America Society, founded in the 1950s. Almost every significant Iranian modernist exhibited their work there. These visual artists were depoliticized, unlike writers and poets, who were much more political, and who would ask: “Who am I working with and where does the money come from?” At the same time, the government is espousing this Eastern, spiritualized ideology, which was defined as the core of Iranian identity, both pre-Islamic and Islamic. The shah of Iran, through the contribution of certain Orientalists in the postwar period, revived this idea that Shia Islam is the continuation of an imaginary pre-Islamic Zoroastrian, Aryan line and thus at the core of Iranian identity. This politics of identity, central to the shah’s project of modernization in the post-coup era, was based in part on the country’s alliance with the United States, but also on spirituality and Oriental lineage. This was appealing for someone like Abby Grey, who wanted to “help,” but who also wanted clean hotel rooms, hygienic city streets, and a bureaucratic arts system that is easy to work with as an American.

VK: I haven’t read Mrs. Grey’s autobiography, but I’m curious about what is missing. Where are the gaps? The art she collected in Turkey is largely informed by two places. One is a particular strand of the State Academy of Fine Arts, Istanbul. The other seems biased to the Gazi School in Ankara. She visited both Istanbul and Ankara but focused in general on academic artists. She also met the most powerful figures. For example, Nurullah Berk was not only an artist but a writer. He also curated the Venice and Sao Pãulo biennials. But, at the same time, she also acquired works from what I may call ex-Ottoman royalty and the early urbanized, who did not share this burden of reinventing the nation. These multilingual, well-educated individuals are well represented in the collection, but when she first visited Turkey, in 1962, it was a very different world from the late 1960s.

LG: It’s also important to remember that Mrs. Grey would usually get her contacts through the local U.S.I.A. [United States Information Agency] branches, finding individuals there who could make introductions. She also collected many prints, and the Turkish art world was very invested in print technologies. And, of course, prints were easy to transport; they could fit into her suitcase.

VK: Prints were a preferred medium, and most Turkish artists neither had the means to buy wide fabric nor the places to put big paintings. It was only in the late 1970s that some artists started scaling up, and the modesty of that particular artistic practice was put aside.

HY: I also have this feeling that she didn’t have this grandiose understanding of herself as a Rockefeller buying art.

LG: No, she didn’t. She absolutely relied on her instincts—she was very upfront about that. Interestingly, she also writes that she realized that a lot of artists were looking at reproductions of Western works in magazines and catalogues. They didn’t have access to real works of art. On her second trip to Turkey, she took along a portfolio of works by Minnesota printmakers. She showed the prints to Turkish artists and organized small exhibitions of them. The Iranian collection, on the other hand, is particularly strong owing to her friendship with Parviz Tanavoli. She established this sculpture foundry in Iran and brought Tanavoli to Minneapolis.

VD: I find it interesting that the power structures in Iran and Turkey made a difference, while power was decentralized in India.

HY: Yes, democracy made everything difficult.

VD: We specialize in that! But that’s also why India continues to be a democracy—as problematic as it is right now. But, it’s important, as Vasif noted, to look closely both at the works she acquired and what she didn’t. It seems to me that there was a certain privileging of abstraction, and abstraction was not that prevalent in India then. Also, Mrs. Grey’s acquisitions connected to U.S. cultural diplomacy at the time and the privileging of abstraction as a symbol of democracy against the social realism of the Soviets. So that kind of decentralized system also in a way didn’t help her get the best works. She also didn’t seem interested, from what I can gather, in Jagdish Swaminathan and the artists who were trying to create another kind of language that is going back and looking at tribal issues or folklore.

LG: But also India is a huge country! For me, I think her biggest impact in India was her support of the First Indian Triennale. She brought over Claes Oldenburg and worked with Ellen Johnson. So, in terms of support, it was not as direct as buying works straight from the artists, but she also organized the first exhibitions of modern Turkish art to travel in the United States, which is extraordinary.

VK: Absolutely. There was one exhibition at the Pennsylvania Academy of the Fine Arts in 1962 called “Contemporary Artists of the Turkish Academy of Fine Arts,” and one small project at the Pascagoula Art Association, Mississippi, in 1964. The artist Muhsin Kut, guide and interpreter during Abby Grey’s 1965 visit, was in the Pascagoula exhibition.

HY: In Iran, a revisionist history of art of that period has yet to be written. Looking at Abby Grey’s collection, you feel that she collected everyone who was worthy of collecting. Siah Armajani, who was living in Minneapolis at the time, told Mrs. Grey that her collection was biased because she acquired works only by artists who exhibited with the Iran–America Society. He urged her to collect the stationery and posters of the Tudeh and Toilers parties. Technically speaking, what Armajani expected Mrs. Grey to collect is not what was considered art. Rather, it was categorized as design. And, of course, this was the primary inspiration of Armajani’s work as a young artist in Tehran in the 1950s. It’s remarkable that the only apparent space in the visual arts where modern practitioners might create something outside of the dominant ideology of the shah and his relatives was in design and stationery. I think that is what Armajani was implying. But as things currently stand, Abby Grey’s collection is the most complete narrative of Iranian modernism that we have outside Iran.

VD: She seems to have been less aware of the political, internal context of what she was encountering but also buys into the American political context in terms of where to go and what she might do. She was also very intuitive and seems to have been drawn to the spiritual.

LG: Yes. She was a devout Episcopalian, and religion was very important to her. Her brother was a minister here in New York, and she became very friendly with the family of the Anglican bishop in Iran, who was Iranian—which is quite unusual—and who lived in Isfahan. I think she related to the spiritual in artists’ work because it resonated for her.

HY: Spirituality in 1960s Iran was understood as the antithesis of Communism. Communism was this materialist ideology that came from the outside, and spiritualism was the opposite of materialism, presumably originating from within a lineage of Iranian identity. Spiritualism became a unifying force behind Iranian history before and after the “invasion” of the country by Islam. But much of the interest in the local identity around spiritualism actually came from a discourse produced by Western thinkers. In the post-coup era, we have Martin Heidegger, whose influence on Iranian thinkers like Ahmad Fardid was marked. Fardid, in turn, influenced Al-e Ahmad’s discussion about Westoxification. More important, we have Henry Corbin, a French Orientalist philosopher who chose Iran as his spiritual home. He lived and worked under the patronage of the shah and wrote a very influential book, En Islam Iranien (In Iranian Islam), which offers a trans-historical account of Iranian spiritual identity. Interestingly, he was paid at the same time by Paul Mellon, who owned shares in the Iranian oil industry. So, spiritualism is both theoretical capital and also grants the flow of oil—Cold War politics in action! This is not to say that these people are hypocrites. During the Cold War, quite a few European intellectuals genuinely sought new understandings of spirituality after the disquieting consequences of National Socialism. I think that this Cold War spiritualism is key to understanding how Abby Grey, either wittingly or unwittingly, functioned within this transnational identity-politics constellation.

VD: I agree. Vis-à-vis India, I find it interesting how Abby Grey’s spiritualism is revealed in how she talks about art. It’s about unification and the meaning of life.

LG: Yes. Her motto, of course, was “One world through art.”

VD: Right. That ideal, and the idea of spiritualism, came together to provide a rationalization of how she saw the world, even if the countries she chose were influenced by the political considerations of others. They were not necessarily her political considerations. She was trying to identify a universal language and, therefore, chose the work that she did. In India in the 1960s, spiritualism was not in the conversation. For the individuals Mrs. Grey encountered, especially in Delhi or Mumbai, the word “spiritualism” immediately meant religious. And if it was religious, then it was against the national conversation about “a secular nation.” People were not even talking about it as a multireligious nation, so this notion of the separation of church and state is very strong in India’s political and cultural circles. As a result, there was almost nothing about the spiritual in art that either theoreticians or intellectuals were talking about even though, one might argue, India, or the subcontinent, is more steeped in ideas of spiritualism than probably any other part of the world. It was more about how Abby Grey thought about it and less about what the artists or the intellectual communities thought about it.

VK: Yes. In Turkey, [Mustafa Kemal] Atatürk, founder of the republic and its first president, initiated radical changes. His government gave women equal civil and political rights. As part of his İnkılaps (Revolutions), he introduced a Latin-based Turkish alphabet, replacing the old script, and Western calendars replaced the Islamic ones. It wasn’t like the Tanzimat era, in the nineteenth century; rather, it was presented as a complete rupture. Early on, artists were the image producers of this long-lasting fantasy. There was a resurgence of this hyper-secularism in the early 1960s, when Turkey tried to institute a new secularist, democratic constitution, and some artists and intellectuals began to look toward the countryside.

VD: So there was almost romanticism?

VK: Yes. There is an image of a kind of naïve—not primitive—innocence. It was prevalent in a lot of the art and in sync with the idea of humanism in the 1960s. But it was not at all like Iran in that way. Meanwhile, on the right, there was quite a sophisticated discourse about the meanings of spiritualism that had no impact on the visual arts.

VD: But, if you’re talking about the past role as a kind of romantic notion, you’re also recovering an authentic identity. In India, some artists were looking at Tantric symbols, but they were looking more to the form than to the meaning behind the form. It wasn’t about bringing the spiritual back in the art, but rather about sourcing Indian subject matter for forms and content.

VK: In Turkey, they understood it as pure form and a generalized reference because they could not read the old script even though calligraphy is employed a lot.

VD: Amazing. But that’s the same idea, right?

HY: It’s not unlike adopting Shia mythologies, like the Saqqakhaneh artists did. It is also manifest in the programming of the Shiraz Art Festival (1967–77), which was posited as an attempt to depoliticize emergent understandings of local cultures and identities. I tend to understand the festival in contrast to the Pan-African Festival of Algiers, insofar as the latter became, in part, a platform for militant understandings of local identities. In the Shiraz Art Festival, there was a huge emphasis on “Eastern cultures.” Eastern artists were invited to put on stage traditional and ritual arts. At the same time, Western artists, like John Cage, Peter Brook, and Robert Wilson, were invited to create the most avant-garde performances there.

VD: Right.

HY: So there was a significant turn toward local identity and understanding this identity as authentic and spiritual but, at the same time, extremely depoliticized. It’s fascinating that all these radical Western artists and practitioners decided to go to Iran and work for a military dictatorship that was in alliance with the West through its anti-Communist politics. They didn’t seem to mind who paid the bills as long as they could create the most radical performances in Persepolis!

LG: I guess it was an invitation that was hard to turn down!

HY: To the locals, many of the performances were controversial, and audiences felt reduced to passive spectators. Eventually, such discontents became politicized and, during the 1979 Revolution, we saw masses of people who could point their fingers at the “Westoxified” government that brought all these “corrupt” Westerners to Iran.

VD: In a way, it relates to what James Clifford has talked about—what is authentic? How we want to put certain cultures in a box of what is authentic. As he puts it, the colonial masters come, westernize the locals, and then deign what they produce as impure. In India, for the longest time, ICCR—the Indian Council for Cultural Relations—sent only traditional art abroad. They never supported anything modern. And to this day, it’s very problematic for them because what is considered authentically Indian is the sitar player.

LG: The “un-Westoxified” arts.

VD: Yes. But let’s return to this notion of art’s capacity to unite. As we noted earlier, what Mrs. Grey didn’t collect in any of these countries is as significant as what she did acquire. In the Indian context, none of the works in the collection gets the particularities of the experience that might be different. Something that might counter her universalist argument for art.

HY: It’s also interesting that Mrs. Grey talked a lot about poetry. But when she went to Iran—which is “the land of poetry”— she didn’t meet with a single poet.

VD: Same thing in India.

HY: Poetry, of course, is linked to the particularity of the language. And while the poets in Iran represented some of the more liberational aspects of nationalism, visual artists were linked to an identity-based mode of nationalism and an “optimistic” belief in the possibility of the universal. This wasn’t the case with poets or even with filmmakers or playwrights, whose works were also based on language.

LG: Language is really crucial in those art forms.

VD: In India it’s complicated because English is a language of the intelligentsia and part of cosmopolitan, city life. But there is very little in what Grey writes about trying to get at other kinds of notions of behavior or cultural life.

LG: I don’t think she met with writers in Turkey either. She was very focused on this idea that the visual doesn’t require language skills. I just reread her autobiography where she recounts her first trip to Europe after college. She’s very proud that her father has given her $1,000, which was supposed to last only the summer, but she stretches it out. She’s able to do this since she and her traveling companion are invited to spend six weeks at the American embassy in Riga, Latvia. There she learns about diplomacy. But when she goes to Paris she talks about one instructor who introduces her to the arts while she’s learning French. But she soon realizes that she needs to have greater fluency to really participate. Obviously, she doesn’t have to learn Turkish or Farsi to be able to travel to Turkey or Iran. But, in the end, the result is that she decides to collect non-Western contemporary art.

VD: But with this notion of universal, somewhat semi-abstract or abstract art which will be accessible to everyone.

LG: Exactly. So, it is this particular prism that we need to keep in mind, one that is formed, in part, in relation to cultural diplomacy.

VD: Her prism was about the expression of freedom, the expression of individuality. And it was not about art at the intersection of state politics, as it was in the Soviet Union. Never mind that in Iran, in Turkey, and in other places, art was also caught up in the domestic political agenda. What interests me about Abby Grey is her particular version of cultural diplomacy. She said she was interested in non-Western contemporary. Why didn’t she travel to other places?

LG: She does. Remember that on her initial trip, in 1960, she also visited Thailand, Cambodia, Kashmir, Nepal, and Pakistan. Later she traveled to Italy, Spain, Greece, Italy, and Tunisia. But the countries she visited the most are Iran, Turkey, and India. So she did find something in those countries that connected with her on some level.

VD: Or that she was encouraged to go back to these countries by her colleagues and friends in the State Department. Her approach to diplomacy seems to have been, “I can make a difference here.” It’s well intentioned but somewhat naive, and that needs to be put on the table.

HY: At the risk of lapsing into personal psychology, I sense that she might also have had a sense of being provincial herself. She didn’t have an understanding of her own work as something really grand; she didn’t set out to transform the art scene in any one country. She traveled to countries where she stood out more than, say, France. She was acknowledged in Iran, Turkey, and India, which helped her self-esteem. And the works she collected aren’t grand—they’re small or medium-size and moderately priced.

VK: But I also assume that modesty was the usual method. At that time, everything would have been put in one crate—whether sixty paintings or sixty etchings—and sent to India. I’m not talking about the big exhibitions with huge paintings, but how art at the time usually circulated. She wasn’t the only one who was collecting on a modest scale.

LG: And it’s interesting how that collection ended up in New York! She was very proud of St. Paul and was very loyal to the city, but—as Robert Littman notes in his interview with Michèle Wong (see pp. 00–00)—the collection came to NYU because of an unusual set of circumstances. For one, Mrs. Grey’s brother was a vicar at St. Luke’s in Manhattan, where she visited frequently, but also she watched NYU Professor Peter Chelkowski lecture on Persian history on Sunrise Semester on CBS, which inspired her to contact the university. The Gallatin Museum of Living Art and the New York University Art Collection set a precedent for original art on the NYU campus. It’s not unlike the particular set of circumstances that allowed Abby to think big and come up with the idea of building a collection of non-Western contemporary art. Certainly, both the Grey Art Gallery and, as it were, the rest of the world are richer for it.