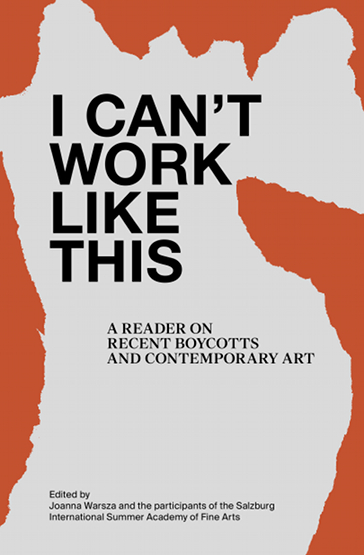

(in conversation with the editors), I can’t Work Like This: A Reader on Recent Boycotts and Contemporary Art, Sternberg Press & Salzburg International Summer Academy of Fine Arts,

Nobody could foresee at the time leading up the 13th Istanbul Biennial, the outbreak of the Gezi Park protests which obviously changed the course of the Biennial and led to a wave of boycotts. Can you tell us a bit about the context of the Istanbul Biennial, before, during, and after the Gezi Park protests?

One aspect of Istanbul, which seems to be different from other contexts of recent boycotts and withdrawals, is the unimaginable state of general political pressure, and particularly pressure on the artists. The context is much more difficult than Moscow or Kyiv, and it’s certainly not the same as Sydney—here, we’re dealing with a different, harsher ecology. The pressure has a history that started with the 1980 dictatorship in Turkey, which led to the evaporation of public space.

The Istanbul Biennials used to function more or less as a “sanitary space.” By sanitary space, I mean it had been immune from everyday political situations. It was a context in which one could do things that were impossible otherwise. The biennials were immune from certain legal processes; this is a shared condition of many biennials: they can operate independently of a specific “institution.” This kind of sanitized space that the Biennial historically provided made it possible to do certain things that would otherwise not be possible; however we should take this with a grain of salt. For example, in the 1992 Biennial of which I was director, or meta-curator, one of the participating artists, Hale Tenger, was hit by a court case on the last day of the exhibition. The court case lasted for about a year and Hale was acquitted of the charge of insulting the Turkish flag. The charge was bogus, but the threat was real.

We should keep in mind that during René Block’s 1995 Biennial there was a project by Maria Eichhorn that was held in public space at Taksim Square, which was sabotaged by the municipal government. In our [with Charles Esche] Biennial in 2005, we brought that project back into our thinking. And one of the projects we hosted was also hit by a court case. The curator, Halil Altındere, and three of the artists were facing serious accusations of crimes against the state and the nation.

Afterward, from 2005 until 2011, things were relatively quiet with the Biennial. One should remember that part of the funding for the Biennial comes from private sources and only a little from local public sources. The other related point is that at the end of 2011 there were general elections in which the Justice and Development Party [AKP] won an absolute majority. After they implemented any change they desired, including constitutional changes, Turkey fell under single-party rule. A lot has happened since 2011, and Fulya Erdemci’s 13th Istanbul Biennial was the first Biennial after the elections.

Before the 2011 elections, the government didn’t care for the Biennial but accepted it mostly because of its promotion of the city. It didn’t matter if the Biennial was critical or not because it allowed the Biennial, Istanbul Modern, and institutions like us [SALT] to flourish. These institutions were addressing a kind of audience that the government was not particularly invested in but didn’t want to do away with either. However, the audience became diversified, and that was a good thing.

Anyhow, after the 2011 elections, those in power no longer needed this kind of constituency, namely the public of the Istanbul Modern and the Biennial. The government focused on inventing “a blissful society,” and a new architecture of power. If you flash forward to the context of Gezi Park, you will see that the reason for the destruction of the trees had to do with the building of a shopping mall in the style of self-orientalizing architecture from the 18th Century. The official urban proposal for Gezi represented the perfect union of an architectural language, mainly pseudo-Oriental and glamorous, the way a European would look at the East. This meant the government could look at themselves through the eyes of the West: a gesture of self-affirmation.

With the government having absolute power and beginning to change everything in the country, foreign policy shifted to the one you see now. The Ministry of Culture changed in 2013, and the brokers between the intelligentsia and the party were all gone. In Taksim Square, next to Gezi Park, you have the Atatürk Cultural Centre, the city’s ultimate secularist, late-modernist opera house. Therefore, in Taksim Square, there is no visual trace of a Sunni Muslim culture. Of course, Muslim culture is present, but the space should be a non-negotiable secular space.

The Biennial before the crisis and the Gezi protests was supposed to take the exhibition into the streets and into public space. Fulya Erdemci had been director of SKOR in the Netherlands and had done many public space projects. “Public” is not the word we use in Turkish because “public” doesn’t exist.

Can you tell us a bit more about this concept of “public space” in Turkey?

The word “public” started as kamusal, which originally meant a space of communion, but the way it was constructed in the 20th Century, it came to mean “state.” Kamu in Turkish means “state” so Kamusal might be understood as “space that belongs to the state,” a space defined by the state’s limits and with the state’s power. The right and the left are still adopting and using these terms, but it’s not a problem of semantics; it’s a problem of cultural transfer. In the old days, in the late empire, what we might call a “public space” was the place around the mosque: that is where collectivity occurred. It’s where the discussions and decisions took place, including secular and non-secular decisions. This was the space, which produced a self-regulated society.

In the twentieth Century, the early republican elites used kamusal, or “public space,” including Taksim Square and Gezi Park, to manifest their power. They placed a monument in the square, in a country where there had never been a statue ever in its history. It was not a statue but a manifestation of power. Then things changed: anything could be appropriated, claimed, reclaimed, and so on, which happened from the late 1960s through the 1970s. But if you look at the history of the square-the ultimate public space- you know how violent it has been. In 1977, thirty people were killed during the May Day celebrations. Between 1977 and 2015, we had only two May Day celebrations; during the other years, there were either curfews imposed on that day or the roads into the square were blocked.

So, how “public” manifests itself is a long story. When you say, “I’m going to make art in public space,” it doesn’t quite mean the same thing as it would elsewhere.

Can you tell us a little more about Fulya Erdemci’s decision to withdraw the Biennial from public space and return it to museum spaces?

Two things happened. One was a series of artist actions by a group called “Public Art Laboratory” that came out against the Biennial. The group started in 2009, laying bare the Biennial’s relationship to money and privatized or “tribal” interests, but it didn’t lay anything bare or say anything we didn’t already know. The same thing was repeated in 2013 by the same collective. Their first action was light, while the second intervention took place in May, about three or four weeks before the Gezi protests, and the people who led the action were thrown out of the meeting room. Fulya and the activists sued and counter-sued each other. Meanwhile, in the summer or fall of 2013, it became evident that during the Gezi protests you would not be able to do an exhibition outdoors. I do support Fulya’s decision to go inside; how she went inside is another issue. Second was what happened between the Biennial and Gezi. The Biennial never fully apologized for kicking the collective out from the room, they simply said they were sorry about it. This was disappointing for many artists.

How did the artists respond to this situation?

Remember that Turkey has the third largest police force in the world: it is nearly as large as the army. It’s undoubtedly not motivational for protestors when you are taken into police custody during a protest in Turkey, as there is going to be a beating, and it is an incredibly abusive process. The judicial system is divided, and if you’re lucky, you might get a good judge, or if you’re unlucky, which is most of the time, you end up with a judge who may be an AKP supporter. You never know which side you will get.

Many people said the Biennial had already taken place with the actions of the Gezi resistance. It made the space public, had visual culture, exhibitions, an infirmary, a kitchen, no money was used, a transport system, and concerts. It had all the things a well-functioning society might need, so we didn’t need a biennial anymore.

In what way could institutions contribute to Gezi?

It was a time to see your place in the world as an institution. Institutions can become extremely weak, fragile, and problematic: you might have found yourself unnecessary. At SALT, we canceled most of our projects for the following year; we stopped and reprogrammed everything inspired by the methods we saw in action. We asked ourselves, “What is a way of thinking that no longer deals with an inside and an outside?” Retaining or performing a sense of publicness was no longer a question of inside or outside art.

A large group of artists, architects, and critics who were a part of Gezi gathered in the “Orange Tent;” they refused to do any work about Gezi, calling it “Gezi pornography.” There was almost a collective decision not to take cameras into public photographing and no drawing- as everything visual would be taken out of context. The great work that came out of Gezi was the Networks of Dispossession by Burak Arikan, an early version of which was shown at the Biennial. It made sense in the context only because it was knowledge that could be taught to other people, through the Graph Commons software, and bring together a large group of people.

It was collective data mapping the relations of capital and power in Turkey?

Yes. Then another work by an artist collective was just a bulldozer that appeared one morning, but no one could say who made it- it was anonymous. Everything that was in the park during the resistance was anonymous, de-authored, and that meant that the park could not be transposed into a work. It only becomes work because of the way people work. So eventually, about three weeks after the police emptied Gezi, Fulya was invited to a public session that took place in a park organized by Orange Tent. Maybe sixty or seventy people were there, and that’s when I think the Biennial no longer felt right. She came and spoke for about half an hour when it should have been a platform for listening and discussing. It’s a generational thing, I might have done the same -we seem to still be in the broadcasting age.

Andrea Phillips’s public program focused on the problems that come with gentrification. It was protested right from the beginning when the protesters claimed that the Biennial itself was part of the problem in a number of ways. Then it was decided to cancel the rest of the public program.

What is your view on canceling the program?

If I were a protester, I would perceive the Biennial as a weak enemy. You can’t possibly go into a real estate conference and undertake this kind of process. It is intelligent to choose a weak enemy, but the enemy in question is not quite the enemy itself. Gentrification is a very Anglo-Saxon word; in Istanbul, we’re not talking about gentrification; we’re talking about the displacement of huge neighborhoods. It’s not like when artists go into a cheap neighborhood and drive up the prices and then five weeks later get kicked out so the affluent can come in. We are talking about state-and city-led displacement of people. It is more like being a refugee in your city. It is entirely different in strategy and scope.

Yes, the Biennial is obviously a part of it, but the majority of construction processes are run by one company, TOKİ, and that’s state funded-it is not even a combination of private and state. The rest of the investment is meagre next to TOKİ. The protestors or performers are taking these weak moments or weak points, and this potentially agonistic relationship, and pushing it to the breaking point. It’s a very intelligent strategy but hard to understand: neither Fulya or Andrea were expecting it.

The same thing happened to us two months earlier. We did an exhibition on political artists and politics from the 1970s. The same kind of collusion took place. The same group came in and spray-painted all over the walls. After they left we erased more than half of the graffiti because we didn’t like the overambitious aesthetic, but then we kept the other half. In a way they were right, because maybe we took an emancipatory, revolutionary moment and pushed it into historical time. We may have taken away the urgency, but with their spray painting, they finished the exhibition, which was quite OK. These people are quite strong and that kind of confrontation might have been impossible for Andrea to deal with. Yet, at the same time, this group is orthodox-they perform and then they leave. After they left, we erased more than half of the graffiti because we didn’t like the overambitious aesthetic, but then we kept the other half.

After the Gezi resistance, you had to withdraw. There were only two options for the Biennial: either cancelation or withdrawal. Artists kindly left that space to the curators. That was the moment Fulya Erdemci did not pick up on; if she had it could have become an amazing project, because they would have realized the urgency of the artists at that moment. The artists’ objective at the time was not to be part of the Biennial-that was not their concern. It was agency and the question of how this agency could be mobilized in intelligent ways. The exhibition could have been completely rethought.

What was the role of social media both in Gezi and the Biennial? Did it function as a third space?

It wasn’t about social networks. Social networks in the context of the protests were something that would tell you not to go down this street or that street, it was something that only tells you a destination. Istanbul’s art world was part of the resistance- they were there; they suffered through it. They did not need anyone else, they did not need a social network.

How can institutions respond after situations like these? How has SALT adapted and have other galleries in Istanbul taken all of this into account? You said you developed something called “methods,” what does that mean?

It was called “method.” I consider myself a good institutional person. I know how institutions work and can push them into the next Century, but what really woke me up was the intelligence of the outside and the intelligence at Gezi- left to their own devices they were remaking the world. In light of these developments, our role as producers has had to be completely rethought. SALT opened in 2011, and I was hoping that by 2016 or 2017 we would be in a position where we could find new effective tools to transform the institution into a commons: a new kind of commons that would take on the running of the institution in a different way. By 2013, we were only two years old, and we were unable to undo institutional arrogance, or the way that an institution’s intelligence emanates from inside out, like a broadcasting system. We hadn’t acted to further the changes. We saw how weak and ineffective we were at doing things by being a broadcast institution with our self-selecting audience.

Are we better now? We have become a little bit better along the way, but we’re still operating as a broad-cast institution. Our institutions don’t deserve to live in the next Century, which is very clear.

So how to go on from here? Every artist wanted to reinvent the Biennial –not to exhibit– to reinvent it. Over 300,000 people came to see that Biennial; it was the biggest and most visited Biennial ever because people saw themselves in the show. You look at yourself in the mirror at the end of the day and you look good. You feel like your voice has been represented or re-articulated, but for me, that is still pornography because it didn’t problematize this imaginary idea of being represented. You are not really represented- you’re just in it-and that appealed to nostalgia. Gezi is not over, it is a process, it is still a process.

Did you ever withdraw or decide not to do something in career?

Yes, of course. Self-censorship works in unseen and professional ways. If you are in the middle or at the end of a project and you cancel it, that is really bad news. But you cannot eliminate projects.

You may go in unexpected directions this way or that, but this is what we do every day. We close certain doors and open others. We try to be strategic; we try to expect the ramifications of what we do, sometimes we take them on and sometimes we don’t. For me, it’s difficult to do certain things because I don’t think I am ever working for any immediate contemporary audience-ever. I have to move between the future and the past. A future and a past are as important as the moment in which you work.

But I have never accepted straight censorship, no, never. That doesn’t make me a better person. At the end of the day you can always trust the public but you can never trust the tribal interests of those who hold the controls. Perhaps sometimes it is the stamina of the institution, or maybe you think it doesn’t make sense to make an avant-gardist gesture because it will actually not produce a discussion. All these things happen. We are supported by tribal interests in one way or another. We know at the end of the day, if the interest or support dies, we will no longer be able to do certain things. I come from a highly privatized cultural sector. 35 years of no state support. 50 years of weak state support. it was only from the mid-1960s that state support was available in Turkey. And I’m still trying to make something good out of that.