16 August 2010

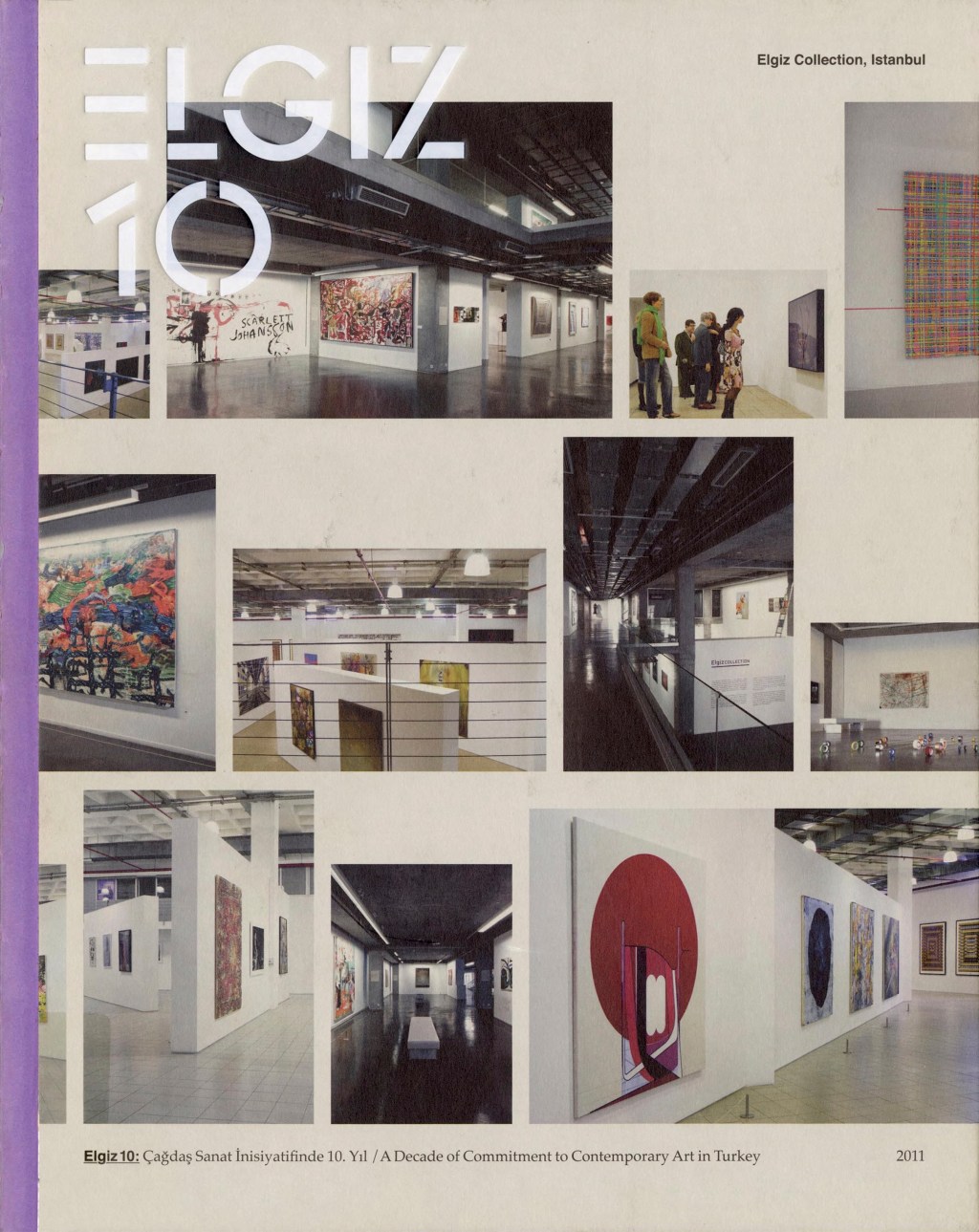

In A Decade of Commitment to Contemporary Art in Turkey, 2011

Vasıf Kortun: Can Bey, more than the history of your collection, I would like to talk about Proje4L. It’s now been 10 years since it was founded. You and I met in 1999; while I was running something called the Istanbul Contemporary Art Project on the third floor of a building in Tünel, you and Yahşi Baraz dropped by one Saturday.

Can Elgiz: We started in September 2001, so September 2011 will mark our 10th year. Of course, I remember the day we met. You had a place full of books where your students would drop in.

Vasıf Kortun: There were students there, and you gave me your card; I saw that you were an architect with a PhD. I wondered who this Can Bey was and did as much research as I could. I called Yahşi Bey and asked him a few questions. At the time, Murat Pilevneli had just gotten back from his service in the army and was about, while also selling paintings on the secondary market. For my part, I was trying to encourage him. Then we both visited you together.

Can Elgiz: That’s right.

Vasıf Kortun: I laid a file in front of you with works by Ayşe Erkmen, Bülent Şangar, Hale Tenger, Halil Altındere, Aydan Murtezaoğlu, Gülsün Karamustafa, and five or six others of that calibre.

Can Elgiz: Strong names.

Vasıf Kortun: Yes, very solid names. You looked at the file and said, ‘I’m not ready for it, but I want to open a space for contemporary art, I mean start a place open to the public.’

Can Elgiz: That wasn’t when we met Murat. He probably dropped in sometime later.

Vasıf Kortun: Or it was the second meeting because I recall afterward telling Murat to withdraw.

Can Elgiz: At that time, I hadn’t started purchasing works, but when I shared my idea of opening an art space with you, it was something you wanted, too. Murat continued with the commercial side, but you and I rolled up our sleeves to start a non-profit institution.

Vasıf Kortun: Right, in 2000-01, we discussed some very lovely plans and projects. We discussed the first space, whether it should be a white cube, its size, and its height. I see you have a hefty archive of correspondence. Plans were being made for the first space at Harmancı Giz. The lower floor was free, so we were considering whether it should be there or one story up. And you rented the lower floor to an advertising firm.

Can Elgiz: Yes, we developed the project for a contemporary art space and drew up draft budgets for the first three years. The first plans included areas for permanent and temporary exhibitions, and we envisaged having four shows a year. We calculated the square footage, along with storage and office space.

Vasıf Kortun: That was in 2000. What were the numbers at that time?

Can Elgiz: There was a real problem here, I mean, the office, the office library was 60 square metres, the storage room 200, the lobby, the small storeroom, the exhibition area was 500, that’s what we were talking about. In other words, 1000 square metres of space…

Vasıf Kortun: Even more, I believe. Can Bey, I remember when you went to fairs when nobody else in Turkey was. When did you start following the scene?

Can Elgiz: I started collecting Turkish works in the late ’80s or early ’90s. Then we started travelling to keep up with what some of the galleries we knew were doing at international fairs. Around then, Roland Augustine came, and we even organised together. Later, we continued to visit specific major art fairs and biennials regularly. The most important motivating force in my life was really and truly loving art. The second thing that made it easier was having our own space. And the desire to be near today’s art.

Looking back, I see it takes more than just a love of art to make this institution operational. Vasıf, when you saw that it could happen, that turned the project into a reality. It wouldn’t have worked without someone like you, who had international connections and contacts in Turkey with the players in contemporary art.

Vasıf Kortun: And, of course, what happened next? We opened in 2001.

Can Elgiz: But there was a lot of activity in 2001 before the opening. Naturally, everything went so fast that when the opening came, there were no lights -Zeki couldn’t bring them, so we used temporary lighting. But we didn’t change the date. That first exhibition was called Becoming A Place.

Vasıf Kortun: And remember, that date more or less coincided with 9/11.

Can Elgiz: Right, we opened on the 21st.

Ten days after 9/11, there were no flights. About a third or a quarter of the people expected at the biennial came. That was precisely when we opened Proje4L. Before that, we had held lectures with speakers like Charles Esche and Chris Dercon.

Vasıf Kortun: The first speaker was Hans Ulrich Obrist. It was May, and there was no air conditioning. He gave a long conference from five in the afternoon until 10 at night.

It was like a marathon. We had a telephone connection with Yona Friedman at the conference. A foreign art figure giving a talk as part of the everyday workings of an art programme—nothing like that had been seen before. People thought that such a connection couldn’t be set up. Not much was going on in terms of contemporary art. In the spring of 2003, I transferred to the board.

Can Elgiz: That was like the board, with Fulya Erdemci and Melih Fereli. Altogether, there were four of us.

Vasıf Kortun: A few shows went that way.

Can Elgiz: Sure, Ali Akay’s exhibition Entre, Fulya’s show Organised Conflict, Halil Altindere’s exhibition I Am Too Sad To Kill You, and Hussein Chalayan’s show. That was it. It was the summer of 2004, and there would be restructuring during the biennial. Looking back at that time between 2001 and 2003, there was a programme devoted more to youth and young artists, and the place was like a Kunsthalle. No one else in Istanbul had that kind of comprehensive operation, neither as a space nor as a stance. That’s still how it is. There was just the Borusan Art Gallery. Borusan had a decent programme. They were good architecturally, and they did very decent international projects once a year, even if they were small scale. Then came Proje4L and Platform. Platform had a different scope, reflecting the academic side of art. It was like a research centre, where everyone researched and looked at files and acquired knowledge and information about artists.

Can Elgiz: Then Borusan closed, and we were left alone. Now, Platform has closed as well. There is a shortfall in Istanbul of places that provide sustained and dynamic support for young artists. Your handicap at the moment is being very remote. It takes a while to get used to using the Metro.

Vasıf Kortun: Okay, I mean, you’ve always thought about your own spaces; at one point, we were trying to open a place in Beyoğlu.

Remember? An annex.

Can Elgiz: That’s right, some people we knew had empty buildings, and we looked

into making use of them.

Vasıf Kortun: If you could return to 2000, would you consider opening a place in the heart of town? Of course, the town center is moving out this way, but the clientele is different.

Can Elgiz: But that’s a matter of financial structure-that is, using the space you own involves a missed opportunity, but it’s one thing to make a monthly payment and another not to collect a payment every month.

Vasıf Kortun: And yet another to both collect and make a payment.

Can Elgiz: Of course, you could arrange things so that your own space brought in income another way and then you could rent somewhere else, but we had designed this place from scratch purely as an art venue; I mean the wall heights, the lighting had been done with that in mind. If we had moved into an existing building, we couldn’t have shown Hüseyin Bahri Alptekin’s work at the opening exhibition.

Vasıf Kortun: You still couldn’t show that one. I mean, it’s impossible.

Can Elgiz: We couldn’t have shown Kutluğ Ataman’s Women Who Wear Wigs, either.

Those are both questions of space. Hussein Chalayan would have been out, too. But I notice that, well, everybody agrees this thing started with us in 2001; no one denies it.

Vasıf Kortun: True, but then you’re not very aggressive, so why should they deny it? How did the experience of owning an institution affect your collecting?

Can Elgiz: Actually, we didn’t mix up the collection with supporting and presenting

contemporary art. Instead, when artists displayed there, we had no thought of acquiring any of their works. Why not? Because we didn’t think it would be ethical to support production and buy it for a reasonable price. All the artists shown there in that era were artists whom I thought highly of. Looking back, I sort of wish we had some work by them, but it was such a narrow circle and such a shallow environment. We didn’t have to answer anybody.

Vasıf Kortun: And the economy must have played a role since we opened in September 2001. There was a significant slowdown for a while. It all had an impact; these weren’t expensive works. I mean, for their time, they must have been very economical.

Can Elgiz: At any rate, the reason I didn’t buy any of the exhibited work at that time

It wasn’t the cost or anything. It was your theory, or rather main idea, that collections could force people to remain fixed, frozen…

Vasıf Kortun: My question was more personal. For example, did you think so highly of those artists in that era, or was it when they developed and your confidence in them grew that you became more interested?

Can Elgiz: No, I mean, at the time, we had confidence in all the artists who exhibited

there, or else we wouldn’t have gone for it anyway.

Vasıf Kortun: You’re talking about confidence…

Can Elgiz: When I say confidence, I mean we liked the work, too. Sometimes, when

my friends came to the shows and didn’t see the work displayed as art, they would ask, ‘Is the exhibition upstairs?’ But that kind of remark didn’t discourage me. If it had, I would not have continued this mission.

Vasıf Kortun: Of course, it was hard because, if I’m not mistaken, there was this kind of pressure on the collectors, on you. I mean, you can have friends, even close friends, who don’t understand and, more importantly, who find what you do to be, at the very least, peculiar.

Can Elgiz: Right. A few years pass, and many people still ask, ‘Why do you do this?’

And explaining to them is even harder.

Vasıf Kortun: Explaining to them is difficult. That’s another form of pressure on you when these initiatives are new.

Can Elgiz: But it’s normal. It allowed people to see artists they couldn’t access through the commercial galleries, which was an advantage. And in the following periods…

Vasıf Kortun: You have got to know them better. Why did you opt to transform the institution into a collection museum? Or rather, do you want to follow the same idea you had when you made that decision, or has there been a change? To me, it seems like there is.

Can Elgiz: Normally, you need a stronger financial setup to run both systems in parallel. On the one hand, you’d have your collecting, and on the other, supporting and displaying these avant-garde works, ahead of their time or above the commercial level. And that offers a comprehensive spectrum. You show work that not everyone sees or finds a chance to exhibit. There was a period when those works, too, would find their way into the commercial category, but…

Vasıf Kortun: Or they might not have.

Can Elgiz: Might not, right? It concerns the artist’s identity there or who they work with. But, of course, there should be space to give people a chance. When collecting becomes your essential calling, the responsibility arises to share the collection with others. Then, of course, our foreign acquaintances tell us we have to show our collection, so we came to that intersection along the way partly for that reason. Of course, if it had been possible, we could have kept up with both sides of the operation, but it wasn’t possible.

Vasıf Kortun: But now, at least, you’re doing both. I mean, right now, that’s how it seems to be.

Can Elgiz: Yes. It’s come a long way, but, well, in other countries, the opening of the Tate, in the world at large, there weren’t that many, not as many contemporary art spaces as there are today.

Vasıf Kortun: No, certainly not. The last 10 years. After the walls came down in ’89, all the change started.

Can Elgiz: In northern Europe, there was Kiasma and Moderna Musset.

Vasıf Kortun: Even Kiasma only opened in ’99.

Can Elgiz: As an older example, you have Moderna Musset in Stockholm.

Vasıf Kortun: The Tate Modern celebrated its 10th anniversary [2010], and the Bilbao Guggenheim had it in 2007. The Guggenheim is an example, but these are different things. I mean, both other and the same. Some operate on money from large foundations, the state, or public money. They’re institutions that redefine their cities. The Bilbao Guggenheim alone brings 1.5 million people to the city annually. Six years ago, that was Istanbul’s total tourist potential. Or take the Tate- annually, it brings in 3.5 to 4 million visitors. Hundreds of thousands, even millions of people, come just for the Tate. Of course, that’s another story.

Can Elgiz: The Tate has formed a bond with its city.

Vasıf Kortun: Those two cities have very similar stories and resemble Istanbul. The business of redefining the city through starchitects traverses that bond by the river, by the cleaning up that river- there you have it, the Tate and the Thames, Istanbul and the Golden Horn, Guggenheim and the river Nervion. These are all roughly similar models. Generally speaking, there is a wish to follow the same model, but the model is a halting, lurching affair with us. Instead of having decent public

intermediaries, everyone says, “I know best,” and we go under. Had things been handled differently, we could have been much better off. But there is one thing: your place is here, and in Istanbul, you’ve got the historical peninsula. There’s nothing like that in the world. The world has no similar archeological museum, no other Hagia Sophia, no Topkapi Museum, or any institution like the Museum of Turkish and Islamic Arts. Such values are found only in New York, Paris, London, Istanbul, and Berlin. That’s a lot. I mean, not even Athens. On the other hand, we’ll never be able to compete with them. We don’t have what it takes to compete with them, so we give the 20th century a kind of miss and try to move into the 21st, shape a different sector in Istanbul made up of scattered institutions like this, a small or medium-sized sector. What we must do, ultimately, is work on models that will consolidate this sector, that is, instead of competing, feed each other passes, make mutual use of equipment pools, joint calendars, maps and so on, or else come together to form a common front against City Hall, the state or the Ministry of Culture, shape a consortium of mega institutions. That’s the only way we’ll get anywhere. But at the same time, it is a massive deficit in our attempt to redefine this city. If people come to Istanbul today, it’s for entirely different reasons. Not just for the history, not for Topkapı Palace. They come to live and experience the city. We knew this 15 years ago, too, but the municipality and the state had their peculiar way of doing things. That’s the reason for the farce of 2010. Not ineptitude; it has to do with this. Let’s revisit your collection. Has there been a significant change in the collection, or are you continuing in the same vein? Are you keeping everything?

Can Elgiz: We’re not removing anything. Right now, there’s not a lot of activity, but we’re making many more purchases. We’re trying to hone in on newer artists who are just emerging. Naturally, those two paths impact one another. Meanwhile, as I say, holding exhibitions by non-commercial artists sort of trains the eye.

Vasıf Kortun: Are you concentrating on certain artists, or are the acquisitions more general? In the past, there were artists, and you had many works by them, all of which were very comprehensive, throughout their periods. Some artists were more heavily represented, even if there were plusses and minuses. The acquisitions weren’t spread out.

Can Elgiz: But there’s nothing like that…

Vasıf Kortun: For example, are you following any one artist seriously?

Can Elgiz: No, we don’t have an art-historical, didactic collection. There’s no concern with completing the spectrum of some movement or completing this or that period by any artist.

Vasıf Kortun: I ask because you might build something around Cindy Sherman, Jonathan Meese, etc. It doesn’t matter which artist you choose, but have you got something like that going? I’m talking about relative weights.

Can Elgiz: Well, there’s more in photography and video. We didn’t have those before. Naturally, they affect one another. Some 10 years ago, there was no photography or video; we had less, but conceptual and other works began to look more acquirable.

Vasıf Kortun: Because really and truly there’s been a change, I mean, stuff you wouldn’t have bought 10 years ago, now you’re acquiring it without a qualm. And things you purchased 10 years ago, you probably wouldn’t have acquired those 20 years ago.

Can Elgiz: Sure, of course.

Vasıf Kortun: We’re talking about a fundamental transformation. Very well, does a collector have a duty vis-à-vis the public?

Can Elgiz: A collector shouldn’t be an investor in art. I make a distinction between the art lover and the collector. The art lover likes to see paintings and art on the walls of their home or sculpture in the room, someone who thoroughly enjoys following the art scene. Some investors think of investing money today and selling tomorrow. The responsibility of a collector towards him or herself is over and above the love of art. And also, concerning their responsibility towards society, the more they support young artists, the more significant their contribution to art will be. Why do we eventually share our collection? That’s an example we’ve imported from abroad- what’s the good of burying your collection in a storeroom and not sharing it with society?

Vasıf Kortun: Anyhow, you’re always going to bury part of it, you have to. You can’t always show everything, but what you’re saying is that’s not your policy, your principle.

Can Elgiz: After purchasing a work of art, it’s never good to store it somewhere. Only, of course, since not everyone can create a space for themselves, how does the system work abroad? Artworks are given to the museums on loan. When they have an artist’s retrospective, they contact all of his or her collectors and gather works from them, so the works see the light of the day, off the walls of their homes or out of their storerooms. But in Turkey, no institutions do this or record who’s bought what. I don’t know a decent record of who has what work or how many works by what artist.

Vasıf Kortun: Okay, so the adventure continues. There’s no stopping. Have you reached your final destination?

Can Elgiz: Well, you never know if it’s final.

Vasıf Kortun: As I see it, you’ll get moving again.

Can Elgiz: If we could expand even more, it would be great. Or at least devote more space to temporary exhibits. But there is a point where you meet a dead end; in a home, too, when you buy new books, they don’t fit in the bookcase, so some stuff goes into a second bookcase, then there’s not enough room to move around. Well, here, too, if you stash the collection in a storeroom, there’s not quite enough space, and it’s no longer on view. Then you’re limited in the space you can set aside for the temporary shows, but you still try to make room. We thought we could do something on the museum’s roof or the grounds, but this is a cold neighbourhood. Cold and windy. You never know, maybe in time we can develop another space. If you think back, you’ll remember that in

Between 2001 and 2005, we didn’t use the family name or anything—no private name, in fact. The reason was to avoid losing the chance for support, sponsors, etc. But then we couldn’t find anything. To some extent, it took the wind out of our sails.

Vasıf Kortun: That was a very modest operation. You know how you were; there was no support to get things moving. Of course, at that time, there was no support anywhere else.

There was no fund. We could only find money for our exhibitions, and that was just barely. That’s why we had some stopgap projects back then. You emphasise two exhibitions, but aside from them, there will be two or three other shows, if you don’t think we’ll do you any particular harm. We had a summer show by the famous Danish designer Arne Jacobsen. We did it in a way with no cost; it was what we called, in quotes, an ‘elephant’, that is, he’d cause no harm, wouldn’t damage our stance but wouldn’t make waves. And we did that vast Çağa show, for example, at the same time as the Çağa family’s, and that, too, was ultimately a good exhibition.

Can Elgiz: Yes, that was a good one, too; a cross-section of Turkish painting.

Vasıf Kortun: An exhibition of a collection of Turkish paintings. We might not have held it under different circumstances, but it let us breathe easier. Of course, programme expenses are always the worst thing in the world. To have one decent event in your programme, you’re forced to do three mediocre things if you want to keep going, that is…

Can Elgiz: Of course, right. This means the public didn’t want to lend support despite there being no other space in Istanbul.

Vasıf Kortun: Such things are remembered later.

Can Elgiz: Yes, in a proper way.

Vasıf Kortun: There was nothing like that in Istanbul. It’s a period etched in everyone’s memory. Even today, when there is something, it’s a relief because there’s still nothing of the sort today. There’s no place open to the young, dynamic people, to those

who have not yet gained acceptance.

Can Elgiz: By ‘not yet gained acceptance, ‘ you mean there’s no one to whom they can

Show non-commercial work?

Vasıf Kortun: Work not yet approved by someone. You show the non-approved things in 10 square metres, but that becomes a statement when you display in 1000 square metres. Okay, what about weaknesses versus successes? Where do you feel you’ve failed?

Can Elgiz: You mean then or later? Or maybe with the collection?

Vasıf Kortun: Well, for example, could we say something like, ‘Vasıf, I should have invested this much more money in this, or we could have hired a very effective public relations firm and done some promotion, we could be really up front and open about it’?

Can Elgiz: Actually, back then, we were talking to some people about PR, but naturally, these are all matters of budget. When someone with a collector’s means has to pay costs, that will prevent him from collecting. You give your heart to this, establish a space, and work with a team, but you need support to keep going. The point is that we don’t do institutional promotion, which would mean setting aside funds. So this comes only from investing your soul in art, from loving it and loving artworks. If you hire a PR firm, you lose that quiet aspect. It became a promotion for Disneyland.

Vasıf Kortun: Everyone’s a little quiet, don’t you think?

Can Elgiz: A bit quiet. [They laugh]

Vasıf Kortun: Well, this personality reflects on the institutional identity.

Can Elgiz: Of course, but trying to be in full view can lead to misunderstandings, and

Suddenly, you find yourself in a different chair altogether. Or rather, you have to sit in a chair that somebody else has put you in, and your goals become skewed. But at the moment, more foreigners than Turks come in, whether to see the collection or other exhibitions, because any foreigner interested in art who comes to Istanbul manages to find us. They visit, ask for information, talk with us, and then leave feeling content. With the Turks, it’s mainly students. In that respect, PR has started to figure out how to proceed. But foreigners come without PR. Anyway, more news appears in magazines and books abroad than we get here. We aim to present the foreign and domestic all together, so when people abroad look at a painting they know next to a Turkish artist, they can better accept them. And if that young, If a Turkish artist is not yet recognised by the market, that, from our standpoint, is a contribution to art.

Vasıf Kortun: Does that happen?

Can Elgiz: Sure, it happens.

Vasıf Kortun: How about being discovered in your place?

Can Elgiz: Since we’re not commercial, we only provide contact. We have a section here for artist portfolios. We did an exhibition on 16 September 2010 with an Italian curator, Elena Forin, for an Italian artist named Giovanni Ozzola. They came entirely of their own accord with support from the Italian Consulate. From the portfolios on hand, we asked if she’d like to choose a few Turkish artists to accompany the Italian artist. She

selected two. Ozzola is a good artist, and Elena Forin, the curator, works at MACRO in Rome. She chose the Turkish artists, and something very gratifying happened; people who came to see Ozzola’s work also saw our collection and the selected Turkish artists’ work. That mission continues, and there’s no slackening of interest. If 10 more years pass, it will still go on, as long as we have the space. One might want to return and have it the way it was in 2001, 2003, 2004. But we need more space.