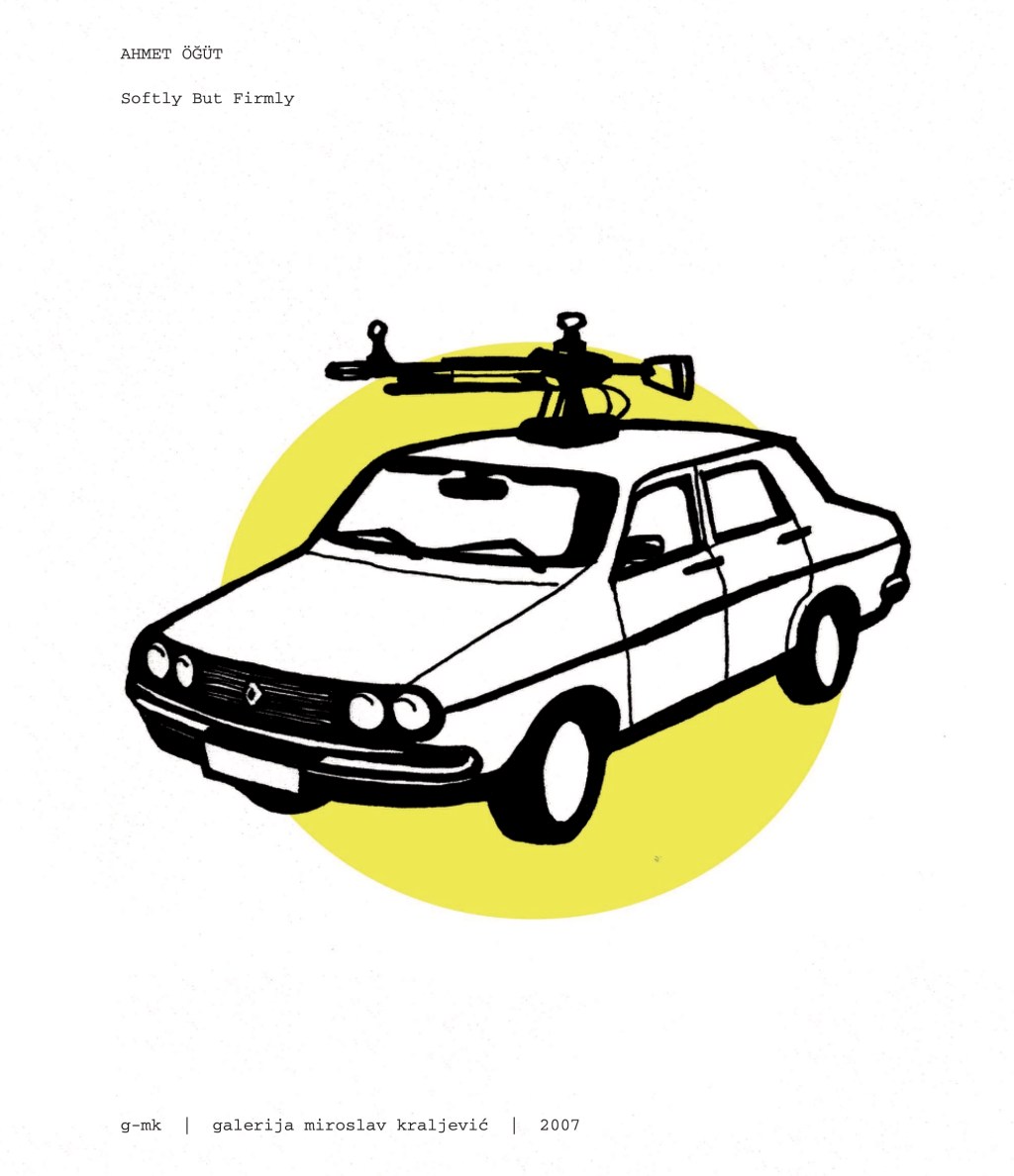

Unpublished, 2006

Vasıf Kortun: Ahmet, “Devrim [Revolution]”[1] reminds me of Vahit Tuna’s work titled “The President`s Car”.

“The President’s Car” reflects not only Vahit’s relationship to his childhood but also the transformation of the luxurious American cars imported to Istanbul. From the late 40s until the end of the 70s in Istanbul, which was a working-class city, those American cars were first owned by the wealthy families; after they were used as taxis, they were finally extended as much as possible in length and used as a kind of minibus with eight seats. In the meantime, they were reproduced in the small city workshops, except for their exterior framework; in other words, they were “hybridized”. I am not talking about a city that has developed a sort of industry or manufactures its vehicles, but am referring to the Dolapdere Istanbul. In your work, there is also a president; this time, it is not Truman but Cemal Gürsel, the President of Turkey! Turkey underwent another revolution after the “Devrim [Revolution]” in 1960 and started manufacturing. However, this car remains a prototype, a single example. In that sense, it is handmade, like a “sculpture”. Looking at the style of the Devrim car, it can be seen that it is an American car outside although it is “produced in Turkey”. After all, once land roads have become dominant, does it mean anything about where that car was produced? This is mainly if an import-based industry, importing various goods such as cars, spare parts, and tires, was formed in such a country.

Is there a relation between the car being handmade and your decision to make a meticulously ‘handmade’ large wall drawing out of a small picture you have found? I mean, both gestures imply a sort of “futility.” The car, which doesn’t move and the ‘imprecise’ wall drawing of the blurry original model? Futility, failure, and the fact that nothing changes at the end of this action/performance show that it is all unnecessary. I am not using such terms in a critical sense, by the way.

At this point, I remembered Hakan Topal’s criticism of “Devrim [Revolution]. “At the end of your talk at Platform Garanti, Hakan said that the work ‘could not go any further, that it did not ‘work’, while you replied that it was all-sufficient indeed. There seems to be a substantial difference regarding the status of art as far as those two points of view are concerned. What would you say?

Ahmet Öğüt: I must say that the work “Devrim [Revolution]” is a sort of byproduct. I produced it as an extension of my drawings published in the Biennial daily under the title “Today in History”. Devrim car also represents the work of a supplier industry. We are from a country characterized by the supplier industry. The mentality that says ‘That will do,’ ‘It will be sufficient,’ We do not need more,’ and ‘We will manage’ is still dominant. We see that many events happened in the country’s history in the period when the “Devrim” car was manufactured in Turkey. In the aftermath of the military coup on 27 May, 1960, a new constitution was adopted on May 27, 1961. Adnan Menderes, the former PM, was executed only a month and a half before the completion of the Devrim car production. Then there is, of course, Cemal Gürsel, who was elected as president after the military intervention. From my point of view, it is not surprising that the president, who had a military background, gave the order to produce a local car in four months’ time. We should not overlook the power of the imagination of former generals who emerged from a legacy of the military junta, like Gürsel. For example, one of them had such a vast scope of creativity that he flew from Hakkari to Ankara on a jet fighter to beat up a soldier and then flew back to Hakkari on the very same day. We have to be aware that at that time, when the government was pressing the production of a local car, there were many against it. The State Planning Institute was disturbed by the decision that clashed with its efforts to save funds. Moreover, the opposition parties’ attitude regarding that decision was, of course, negative, and finally, there were many conspiracy theories related to the giant automobile brands, such as Ford and Chrysler that had a dominating position in the automobile market in the country. It was apparent that all of these parties were against the idea. Although I was aware of all this, what drew my attention to this subject was the science-fiction-like structure of the car’s production and its story. It reminds me of an amulet, a charm prepared successfully but not working, or a spacecraft failing to take off as it lacks engine boosters. In that sense, “Devrim” is very much different from the “Anadol” car, which was mass manufactured later. “Anadol” is a real car designed and manufactured later. But “Devrim” is still a car in every sense of the word. As you have pointed out, it resembles an American car, but what makes “Devrim” different is that it was handmade. It was produced while being imagined, by working directly on the prototype and hammering it into shape. This self-styled production is, in a sense, the definition of the style of production I have always dreamed of.

Like “Devrim,” I have only seen the pictures of Vahit Tuna’s “The President’s Car.” As you have put it, the love for automobiles became traditional in Turkey as a practice of appropriation rather than a practice of creating an industry. The “hybridization” you have referred to is still valid in Turkey. I mean, today, the Şahin car model is modified to resemble the “Doğan” car model. This is the current version of this hybridization.

I increased the size of the “Devrim” car by drawing it from a small picture of 4 x 6 cm to the size of the wall’s surface. This means that I partly used my imagination and drew the wall painting without fully seeing the original car—just like the workers at the wagon factory were producing the parts of the “Devrim” car according to the engineers’ directions. I did not intend to get a new story out of it. That is what Hakan Topal expects from an artist: more of it. However, I was only trying to iconize an “absurd object” once again, and I was doing that by using my hands-—it was about to be lost in time and history. We are talking about the story of failure, and the only way that seems natural to me is to display it in a “futile” fashion. In my opinion, one needs to take the attitude required by the work. I remember what Farhad Kalantary once said: “The butter on the bread should be spread in the right thickness.”

Vasıf Kortun: I suppose Hakan Topal reads the relationship between the work and the subject differently. He sees the theme of the work as a transporter. However, you are pointing out that the attitude is the transporter itself. This is a different kind of thinking, a more crooked perspective.

Let’s talk about the “Death Kit Train” video. It shows a car failing to move, which is another “futility.” However, it is not only one or two people pushing the car; there are many people pushing it. The ones in the front of the line are pushing the car, while the ones at the back are pushing the ones pushing the car. They support each other and do the job together. You know Francis Alys’s work titled “Faith Can Move Mountains.” The title is quoted from the Gospel. In Alys’s work, 500 volunteers moved a giant sand hill about 10 centimeters ahead. Cuauhtémoc Medina touches on this work and says, “A desperate situation calls for an absurd solution.” I know that I have kind of wandered off the subject now. I am now referring to the feelings of desperateness and absurdity instead of the work itself.

Ahmet Öğüt: “The Death Kit Train” is more than a story of “desperateness” or “futility.” The ones at the back of the line push each other, although the number of the ones pushing the car at the front is sufficient to move the car. Now, back to the bleak title of the video; it refers to freight trains carrying giant, apocalyptic industrial or military vehicles. Those trains could resemble a porter, but the one with more strength than usual. The number of people carrying a coffin is also more than those needed to hold it. The reason for this increase in the number of people is that what is carried is no longer a worldly object – it has been transformed into something different. The number of people pushing the car is also bigger than needed. I mean that while watching the video, one first supposes that the vehicle is moving independently. But once we have realized that people are pushing the car and then later see the ones pushing the people pushing the car, both those people pushing the car and the people pushing each other are transformed into something different. As a result, the action misses its goal and creates its meaning. It begins to seek a meaning of its own that is beyond its apparent goal. Like the theatre of the absurd, I am trying to talk about a new way of finding “hope” by being inspired by a situation that might initially seem pessimistic. I am looking for this finding of “hope” by being inspired by what is dejected, crestfallen, hopeless, futile, or grotesque. The faith that keeps the ones pushing the car together stems from that point—seeing a collective dream despite everything.

Vasıf Kortun: But there might be a problem here. In Turkish, we might call it “Ölü Teçhizat Treni” but the English translation of the work, “Death Kit Train,” has two references. Besides your explanation, it is also the song’s title.

I would also like to talk to you about your photographs. In the pictures you made with Osman Doğu Bingöl, there is a similar situation, but, unlike the videos or the wall paintings, there is no situation determined before. A fickle kind of absurdity is staged. In “What A Lovely Day,” it is imagined. I am not posing this question to systemize and to apply it to your every work, but I must say that multi-layered humor and the absurdity, which do not despise themselves, are sensed in almost all of them. Please tell me something more about it.

I would also like to touch upon the subject of the asphalt project, which has yet to materialize. Paving asphalt in the gallery, exhibiting a commuter bus fully packed with people inside the gallery, the photographs of people sleeping in the luggage compartment of the intercity buses, etc. Where does this passion for land roads come from? I would like to know what is there besides the emigration, the intercity, the city bus travels and experiencing them.

Ahmet Öğüt: Well, yes. “Death Kit Train” is also the name of a song by Cul De Sac. I sensed a coincidental relationship between the music and my video. Who knows, maybe one might come across the song and think about a similar analogy someday. But it is not essential.

The passion for the land roads? About three years ago, I was traveling to Ankara by the Southern Express train, and the train came to a sudden halt two hours after we had left Istanbul. It was night, and it was snowing heavily. We had to wait in that spot for fifteen hours. Those were the longest 15 hours of my life. In Istanbul, I am a commuter, and I travel from the Asian side of the city to the European side every day, and as I look at the traffic, I think to myself, “How come we manage to make the world such a miserable place for ourselves?” I keep asking myself this question, and now I have realized that the formula is more complicated than a simple equation of road=speed/time. What keeps my curiosity alive is that I am obsessed with the answer to this question: what do distance and “zeitgeist” mean to me?

As for asphalt, it has an institutional meaning related to the public and state. We do not connect it to the province. It is also ideological. Saudi Arabia, the country producing the most oil in the world, does not have asphalt-paved roads. In my opinion, the meaning of asphalt is “safe and secure ground, place defined by the state.” I want to pave asphalt on the ground of the art gallery for this kind of safety. Apart from the wish to make a gallery into a real public space-—a sort of safe place where people will not be afraid of stepping in—I would also want to give a different and new visibility to its existence.

Concerning the photographs I made with Osman Doğu Bingöl, I must say that everything happened spontaneously. We tried to showcase ‘photographic dialogues’ in our environment that simulated absurd vandalistic situations resembling some momentary reactions. “What A Lovely Day” is a telepathic work. What I am referring to is not empathy. It points to a potential guilty feeling. The student questioned in the video also witnessed this feeling. As for my other works, such as the fully packed commuter bus or the students taking an exam during the exhibition opening at the K2 Art Center, I would say that they lead to unexpected encounters.