Booklet, Hammer Projects, Los Angeles, 2006

In 1997 the fifth Istanbul Biennial broke once and for all the domination of the secular, Western artistic elite in Turkey. Halil Altindere, a young artist from the southeast of the country, enlarged his national identity card to placard scale and duplicated it six times. In the section where his photograph should have been were a series of self-portraits that gradually, over the course of the six panels, left his identity behind. It may not have been the most novel piece in the exhibition, but it was the boldest display of Kurdish presence in contemporary art. (Turkish viewers would have understood from the birthplace listed on the card that the artist was most likely Kurdish, and his birth date is given as 0.01.1971, indicating that he was registered with the authorities after his birth.) In the more than eight years since the biennial, Kurdish artists living and working in the southeast have helped to diversify and radicalize the panorama of contemporary art in Turkey. While some of the works, especially those that reference political cartoons, have been one-liners or have suffered from over-the-top humor, those by such artists as Fikret Atay and Ahmet Ögüt have been able to complicate, convert, and reroute real-life traumas, thus escaping the burden of existing to serve as an example.

At the end of 2002 I curated an exhibition in Istanbul of work by lesser-known artists from Turkey. The title of the show, Under the Beach, the Pavement, a reversal of the Situationist slogan, implied the inability to dream of another world, the breach between the promise and the reality of globalization, and how artists operate to insert themselves back into the system. Atay was one of the artists featured, and it was his first exhibition. The work arrived as a video, the cheapest of all formats, via Altındere, who has established relationships with many of his contemporaries, Kurdish and otherwise. Now you have to understand the utter impossibility not only of producing work but also of sharing it and making it public in Atay’s context, let alone the absurdity of earning a BA in fine arts in order to become a teacher in a nearby town.

The work was called Pumps. Its title and title sequence were appropriated from a 1970s adult movie. Shown on a twelve-inch LCD, it was based on a performance in which the artist assesses from a distance an oil pump drilling away rhythmically in a forbidden zone and finally jumps on the pump in an effort to stop it. The pump keeps on siphoning the oil. Atay looks tiny and irrelevant, having reacted in a way only Don Quixote would have dreamt of.

This action took place near Batman, Atay’s hometown. Close to major oil fields and the site of refineries established in the 1950s, Batman was a city living under horrid conditions and a hotbed of terrorism and counterterrorism.

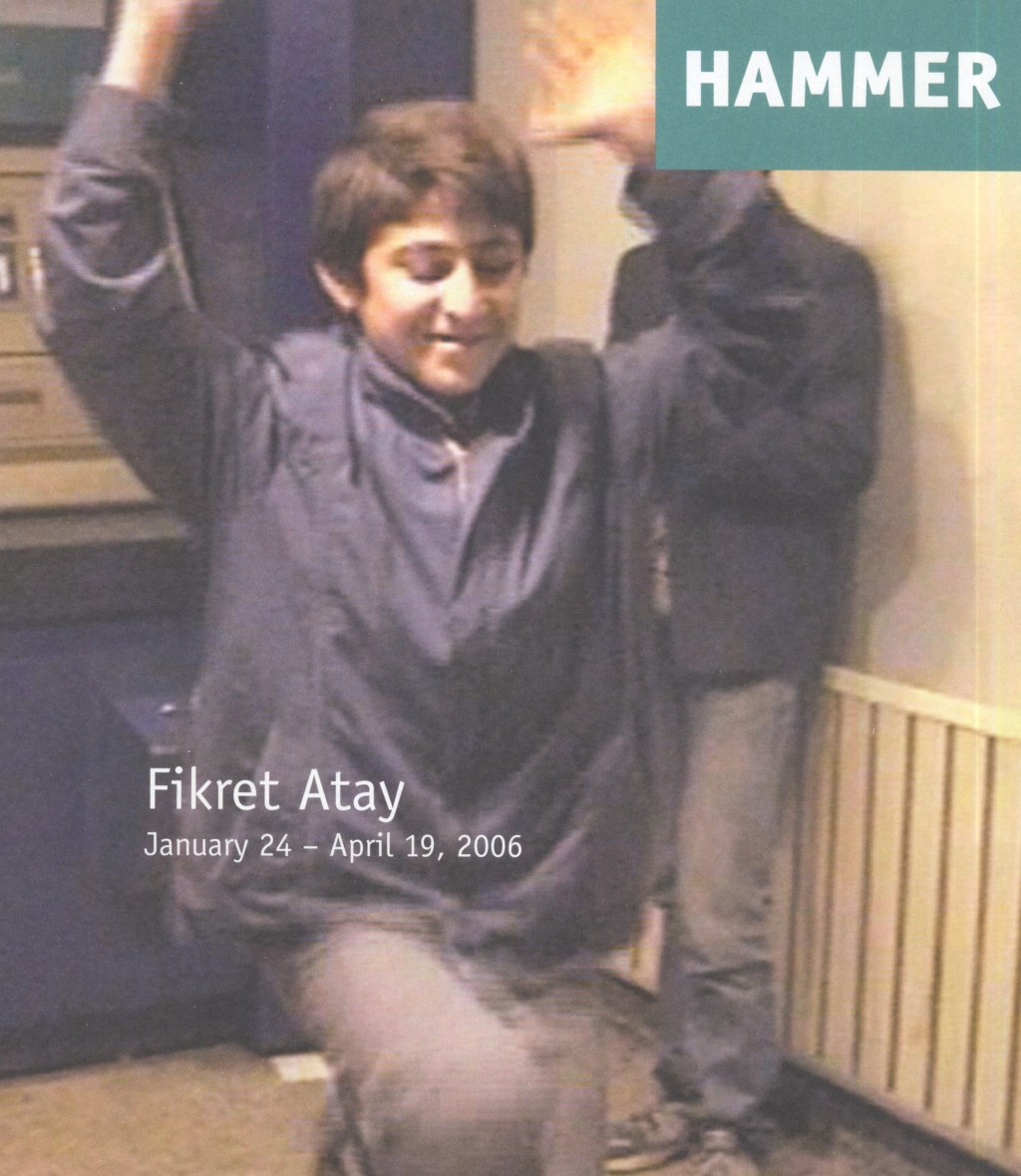

The work was made during a time when Atay would snatch his father’s keys; steal the family video camera, which was kept under lock and key; shoot videos during the day; and return the equipment before sundown. Hence, everything had to be done prudently and planned in advance, with each scene shot in one take. Furthermore, Atay bypassed local exhibition venues and sent his works to Istanbul. In the spring of 2003 two more works by Atay arrived through Altındere. They were Rebels of the Dance and Fast and Best. The title of Rebels of the Dance was derived from Sultans of the Dance, a folklore-derived extravaganza featuring ninety dancers, which was a smash hit in Turkey. The cast of Reb els consisted of two street-smart kids taking refuge in a warm ATM booth. Under grim lights, they break into a traditional song with nonsensical sounds and turn the space into a stage. Their sounds, in full harmony, stop at the threshold of communication, yet, unlike the parrot, a voice without a soul, these performers realize the potential of language at the end of the song “Who Is the Pasha, Who Is the Valet” in Kurdish. The other work, Fast and Best, came on the heels of the invasion of Iraq, whose borders were less than one hundred kilometers away from where Atay lived. A group of young people, boys and girls, dance to the rhythm of a drum in indistinct clothing. They perform in perfect harmony and unison, and together convey a sense of tight-knit community.

Atay left the question of intent open in Fast and Best and achieved the unexpected. Never engaging in the prototypical one-liner or succumbing to the charms of the fast and clever work or the inevitable documentary, Atay keeps his terms of play focused on cultural traditions with an emphasis on the childlike and the improbable. He does not play the role of the Kurdish artist, but the placedness of his works, and the dreamy diversity of his references, produces such a surplus that one does not quite know what to make of it. Bang! Bang! followed in late 2003. Shot with a wobbly camera in the style of live war coverage or cop TV, the video shows kids playing war games in a railway depot, running around train cars, ducking under rails. The gunfire sounds that the boys emulate and they are no strangers to these sounds-fill the air. The memory of trauma is all too present, making the sublimation all the more powerful, and these are the very trains that carry oil out from Batman and that take its soldiers to the city. The title is an allusion to Nancy Sinatra’s song “Bang, Bang (My Baby Shot Me Down).”

The imaginary returns once again in Tinica (2004). A young man stands on a hill overlooking Batman. He prepares with utmost care a makeshift drum set from used cans, plastic bottles, and container covers. He sits to play, but the town is indifferent to the heroics of rock and roll. It is only acoustic after all-it is not Metallica and his call is drowned by the geography. Upon finishing the song, he kicks the drum set down the hill in total detachment. The cans and bottles roll in the direction of the town. The drumsticks are yanked away in disdain. They are thrown not to the competing hands of fans, but to the junkyard of a town deaf to his desire. Time to get out of there.

In Lalo’s Story (2004), Atay has friends perform a dengbej. This is the traditional way of storytelling in song form from the elder to the younger, a way to revive and renew myths. Many such dengbej myths have been updated through the years of war and trauma. Atay turns it into an act by speaking in choppy English over the voice of the performer, who sings about the authorities’ wrongs against a proud father. We can understand everything and nothing at the same time. Within a seemingly simplistic perspective- tive Atay presents a folklore that is infected. He refuses to be pinned down while he is speaking to you from a specific time and place. While it is clear that the geographical location defines the work, it is never disclosed and is never suggestive. Atay plays with language and cultural codes in a similar way: he uses them openly while managing to float clear of creating works that wade in references. You can always get a bit of the story, and that is fine, but you cannot invade the work with what you understand.