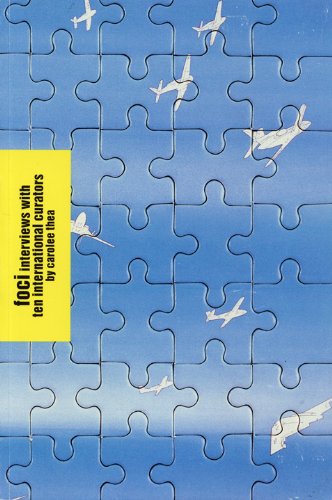

Foci: Interviews with ten international curators

Carolee Thea, 2001

Foci: Interviews With 10 International Curators Paperback – September 15, 2001

by Carolee Thea (Author), Gregory Williams (Editor), Barry Schwabsky (Foreword)

Foci gathers together interviews with ten of the most renowned curators working internationally in the field of contemporary art. The interviews are rich with wide-ranging dialogue and cover issues such as the relationship between the exhibit and its location, art as the barometer for the age, the role of architecture, fashion and design in shaping art, the notions of national and gender identity in art, as well as more specific issues concerning personal curatorial styles. Interviews with Kasper Koenig, Rosa Martinez, Hou Hanru, Harald Szeemann, Vasif Kortun, Maria Hlavajova, Hans Ulrich Obrist, Dan Cameron, Yuko Hasegawa and Barbara London give the reader a fascinating insight into the work and thought process of some of the most creative individuals in today’s art world.

Vasıf Kortun: The Istanbul Contemporary Art Project Center, which I started in 1998 after I returned from my work at the Center for Curatorial Studies, maintains the archives of contemporary artists from Turkey, almost 40 artists. We have a “research” wing, a small library, and international periodicals arrive each month. The research is based on maintaining some memory of contemporary art in all of Turkey. An aspect of this is to archive the present day and look at the past to see what we can salvage. For example, we have an oral history project where we interview artists who are not on the commercial circuit.

Carolee Thea: Do the archives include the works of international contemporary artists and historical and contemporary Turkish artists? Where do you draw your line?

Vasıf Kortun: There are a couple of lines. Firstly, our critical moment is 1968. The older generation of artists were in school around that time. The oral history project records that moment, answering questions such as: what were they looking at? What was the publishing situation? Who were they reading? Who were the writers they spoke to? What films did they watch? What groups were being formed? And, we take it from 1968 to 1987, the first Biennial in Istanbul…

Carolee Thea: Who curated that Biennial?

VK: Beral Madra. She did the first two, but they were not “curatorial” projects.

CT: What was the stimulus for Beral to do an International scale exhibition?

VK: The Biennial was the product of a momentum of exhibitions cropping up; the Foundation for Culture and Art, the mother organization behind the biennial, had already incorporated exhibitions into its various other activities. The biennial was part of this branching out, and it was their initiative. When students graduate from school today, they don’t know this past, so our idea is to turn this research into a publication to chart the changes. It was an international show but not so precise.

CT: What do you mean?

VK: It was a series of divided exhibitions that followed the general model of contemporary art in historic sites and blue-chip artists. The ones in the historical town, especially Hagia Eireni, the Yerebatan Cistern, and the gates of Hagia Sophia, were the real international parts of the exhibition.

CT: Did Beral have a committee, or did she invite the artists herself?

VK: There was a committee, but it could not have been done without her. She became the de facto curator.

CT: Did the biennials get international recognition?

VK: Progressively, more each time. The 1987 one didn’t get so much attention, but it improved in 1989. With 1992, the confirmation/legitimization by the international press was enormous. (This is the one I curated.)

CT: Did Beral hand you the curatorial baton?

VK: Which baton? No. The foundation decided to go with a new person. At that time, the local reaction to an international exhibition was stronger than it is now. There was an operational provincial market with products and collectors, and local powers were much stronger. Beral was chastised, as I would be later on! In the late eighties, many dictatorships were dying or fading away, mutating into neo-liberal political systems. There was a lot of money around and a boom in provincial collections. The biennial evidently intervened in this social space and problematized it, although having been an agent of the neo-liberal economy!

CT: I imagine that the international work was threatening to the art culture of Istanbul?

VK: When you’re in an isolated place with only local truths prevailing, things are pretty harmonious. But when the walls start to come down, and suddenly, new work, culture, and visual proposals flood the situation, the biennial becomes a threat naturally.

CT: Has the international work taken over?

VK: Well, I don’t know what international means, but contemporary art as possible languages are more available now. Of course, it was not only the Biennial that had new proposals. Sarkis’ “Çaylak Sokak” installation in February at the Maçka Art Gallery in 1986 was a significant signal of change.

CT: Tell me about this.

VK: Well, he had been living and working abroad since the end of the 1960s, but he never had a one-person show here, and indeed not a significant installation of personal revisitation. All was fine because although Sarkis was Turkey’s only internationally known artist, he did not have the context to show in Turkey. Others lived abroad, too, but most were only shown and sold in Turkey. So, when Sarkis did this work, which was later installed at the “Magiciens de la Terre,” it became a mark of intervention in an exhibition milieu dominated by local interest! Now, it was certainly not the first contemporary art exhibition, but the fact of Sarkis amplified its significance. Some isolationist locals hit back later with a smear campaign saying that Sarkis was an Armenian sympathizer, “a dagger in our loins.” Taken to court, they paid back dearly for that. In retrospect, that chapter in the history of contemporary art in Turkey was all about xenophobia. Contemporary was alien, folks like me were aliens, the biennial was alien?

The good thing is that they used to think they were in the same league, but they’re not. It’s like the galleries on West Broadway in New York. They sell these things called art to gullible tourists.

CT: Tourist art as opposed to…

VK: As opposed to contemporary art. At one time, the two were indistinguishable. But this was not a situation specific to Turkey alone.

CT: The confusion resulting from the explosion of information is not only related to the internet but also to the falling of the wall. The infrastructure of the planet’s geopolitics collapsed, and now we’re in a post-post-era. The Manifesto, for example, is a post-Cold War European Biennial as opposed to Documenta, a Post-war exhibition. Things change!

VK: Yes, I guess this division wasn’t as clear in the first two biennials. There had to be more distinctions as to what was contemporary and modern, and so forth.

CT: Istanbul is situated in a significant geographic position…

VK: Between east and west?

CT: It is clearly a geographic crossroads between east and west; the city sits both on Asian and European continents.

VK: Yes, geographically that way, but not mentally. These terms don’t make sense in Istanbul because we cross continents daily. The Bosporus Strait also separates the north and south. The Black Sea and the Aegean. Something often overlooked. So Turkey is also between the Slavic and the Mediterranean climates. This aspect is at least as important as the east/west situation.

CT: The Russians didn?t have access to the Mediterranean unless they traveled through the Bosporus, so Turkey has always been in a vital position and most currently during the cold war. Tell me about the affect of Istanbul?s geography on the Biennial.

VK: I wanted to be treated equally when I did the third Biennial. There’s a French term “Bon pour l’Orient?” or good enough for the Orient. I didn’t want that attitude. That was fundamental. Second, I didn’t want to use the historical sites for exhibitions because they serve a touristic cognition. The historical town, the Theodosian city, is not where the city’s people go. I was very tired of this idea of contemporary art in historical sites, and it was overdone all over Europe. I had to re-orient the intellectual position of Istanbul. For example, Turkey’s proximity to the Balkans and the north used to be overlooked by the vertical order of culture. Under bureaucratic socialism, there was a wall between us, but we shared so much of the past. The biennial must take account of the Balkans and Russians. Also, the reality of the city is that it was full of Rumanians and Bulgarians at that time. They came here in the logic of an underground, barter economy, bringing things in their suitcases. This must have its intellectual counterpart, I believed. So, we included Romania, Bulgaria, and Russia and tried to include Slovakia, with the war just beginning in Sarajevo, Bosnia was negotiated, but was impossible.

CT: How did you go about choosing the artists for the 1992 Biennial?

VK: I didn’t have the budget or the knowledge to curate the exhibition myself; I also didn’t want the Cairo/Venice model with national pavilions. The nation-based proposal was not what I was after, and I didn’t have the funds to do what I wanted. As a curator living in Turkey, I didn’t have the audacity to fly all over the globe and bring everything here as I don’t believe one can understand a country in a three-day visit. So, I went to artists and curators and tried to build a community of understanding. These people were great, and I became a conduit. The overall theme was “The Production of Cultural Difference.”

CT: This exhibition was an interesting inclusion into globalist thinking.

VK: Yes, I had seen the “Magiciens de la Terre,” and had been following other projects like the “Decade Show,” and either peeking in on participating in a formative series of conferences for me. But the Magiciens was decisive, the first major post-colonialist exhibition I knew of at the time. It had a lot of flaws but was a beautiful Failure nevertheless.

CT: To what do you attribute its failure?

VK: The logic of the selection process. You know, not all cultural translators in the so-called third world are colonialists, self-colonizing agents, or culturally dominant elites. There are people you can trust, but they overlook this fact as if post-colonial thinking can only be perceived by Europeans and Americans! Secondly, they chose all their magician “others” from non-urban situations or paradigms. Hey, the so-called third world is the new urbanism!

CT: Was the work of urban cultures contaminated by modernist principles, and thus considered inauthentic to the country? Or were Martin’s choices simply post-colonial ideas?

VK: They lead themselves to believe that all the work of urban cultures is contaminated by modernist principles. The real thing would have to be closer to authentic possibilities. Fantastic, no? You posit a singular modernism first and allow no deviation or other modernisms; it is the good old authorship. So. Coming back to my show, after the contacts and deep discussions with, let’s say, the non-institutionalized, non-governmental related agents/curators, we constructed these parts of the how very precisely. The idea was to establish the situation first and then find the money.

CT: Was that difficult?

VK: It worked to an extent. Romania, Bulgaria, and Russia devised brilliant proposals that made great sense during the biennial. The exhibition was situated on about 5000 square meters of one site and had about 72 artists. We created porous wall setups so there would be visibility from one country to the next, and you could see through visually from one section to another. The additional idea was to create an installation plan so that, like Istanbul, visitors would constantly turn corners until they lost their sense of east, west, or north and south. I wanted to do away with this touristic cognition, so we did the exhibition design with Mehmet Doğu, a Princeton graduate. But, the architect for the restoration of the building, Gae Aulenti, wanted to show “her building,” and she Hausmannized the exhibition by cutting an artery through it.

CT: Did Rene Bloch, the curator or the following exhibition, use the same format for the his Biennial?

VK: René took the next step and eliminated the national idea. He chose artists, not countries.

CT: Did certain countries feel they are lacking representation?

VK: Of course, there’s always that possibility. But an exhibition is about the chemistry and the openness of the curator, and it is not only about singular works but also about the climate in which they exist. You can’t have it all.

CT: For the first three Biennials in Turkey, there were Turkish curators. Why now are curators chosen from other countries to do the Istanbul Biennial?

VK: Well, I’m not on the selection committee. But I don’t believe that international shows must have national curators because of where they occur. Different people provide different visions that may be overlooked by someone who lives here.

CT: If they asked you to curate the next Biennial, how would you handle it?

VK: (Laughs) I couldn’t do it; I don’t think I can speak on behalf of the whole globe or even claim to understand it. Then, when you have professionals representing different parts of the world, it can become a boring assemblage. I would change the structure completely, spread it over two years, do smaller projects, tie those to the city to institutions, stress informal educational programs, and emphasize different cooperation and visual intervention modalities.

CT: There are a lot of the same artists in these gigantic international exhibitions now…

VK: That’s the international Biennial Syndrome.

CT: From what you said it’s impossible to go around and choose, and some of the curators appoint directors who go to different places to choose. This happened in Johannesburg and in Kwangju.

VK: Relative degrees of failure; we did the same thing in Sao Paolo in 1998. I was a co-curator for the Middle East for the Roteiros section. Routes, said seven times to connote the seven parts of the world. We didn’t find the proper connectivity between us, despite the goodwill of the chief curator, Paolo Herkenhoff.

CT: Maybe the biennials should pose questions not answers . They are for explorations and dialogue…

VK: There are many problems with Biennials. They’re like easy grounds for professionals, like tourists. You hop from show to show and see the same people. It’s not working. There are also political problems; they are too easy.

CT: Biennials don’t change the state of human rights…

VK: Yes, but it’s the pleasant face, the nice, good, tourist-friendly face of those towns. Yes, Biennials can open things up, but they also conceal things.

CT: Vasif, if the city is opened up then less can be concealed.

VK: It is an issue of the opening mechanisms and delicately designed censorship forms. I would like to see all of you in Istanbul when there is no Biennial.

CT: Geography and funding makes that difficult. You worked at Bard?s Center for Curatorial studies at the Museum. It was a new program then.

VK: It was the first accredited institution in the United States. I worked with Norton Batkin, who was and is the director of the graduate academic program at Bard. I ran the exhibitions program and library and museum matters. There was a linkage between the two. It works pretty well. After four years, I left, burnt out from fundraising and administration. I had my eye on returning to Istanbul, being closer to artists, and starting an institution.

CT: Tell me about it.

VK: ICAP, the Istanbul Contemporary Art Project, is a super low-maintenance, volunteer-based place. We publish a magazine. The important thing for me at this time was not to have an exhibition hall. I don’t do exhibitions when I’m not convinced. I’ve only done shows when I had a problem. I’m unprofessional that way. Once I’m concerned about something, then I can do it. Often, when I’m invited to do something, I think it’s a flop.

CT: Since you’ve been back in Istanbul, have you curated many shows?

VK: A few. One was in this office with 28 artists called One Special Day. Like a journal, the artists had to do their work on September 1—an arbitrary day. The exhibition had four parts: text, audio, things you can carry, and images. However, I also asked the artist to move away from his/her everyday style.

CT: Do you feel as if you?ve made a difference in Istanbul? Was there an arts center here before?

VK: We are not an arts center, but there are centers that I don’t respect. The change is not up to me to say. My position is different because I work intimately with artists, so much so that I sometimes feel I can intervene in the production of the work.

CT: Editing or collaborating?

VK: If you see work that is growing toward something, then you want to get involved in the process. I am not good at collaborating. I don’t have ideas; I only see ideas and build upon them.

CT: Give me an example of how you create a show, what is your process?

VK: No show is alike, no knowable process for me. I don’t believe in a singular position. Starting point is always different, the motivations are diverse, the level of curatorial involvement varies, and so does your understanding of sharing responsibility. When I was at the Institute of Fine Arts, NYU, for graduate work, a well-known professor (and curator) said, “don’t trust the artist.” The reverse is my motto. School For me it’s always about inventing new modalities for looking at things. The worst thing is repetition.