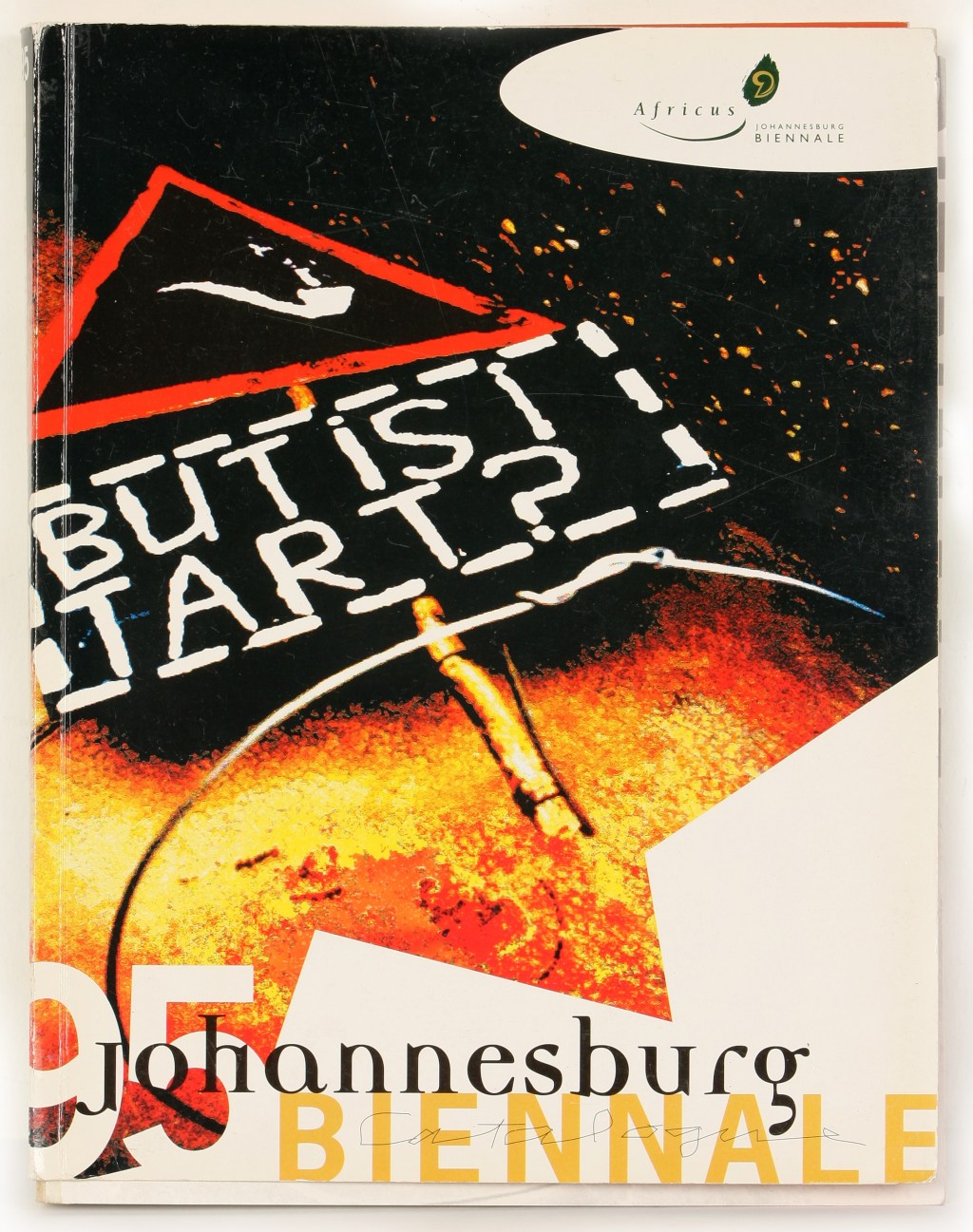

in Trade Routes: History and Geography Johannesburg Biennale. [Exhibition catalogue] Johannesburg: Africus Institute for Contemporary Art. 1997

Are we to enter the third millennium with a national conscience that is little more than a bunch of rags from the scrap heap of the nineteenth century, a costume patched together by the intellectuals of the first half of the twentieth century so that we would not show up naked in the nationalist carnival?

—Roger Bartra, The Cage of Melancholy, Rutgers University Press, 1992

The crisis of cultural equivalency is not only generated by the innate mechanisms of the contemporary art institution but also as a consequence of the entire establishment of global liberalization. Globalization as a master plan has been in effect since the end of World War II, eventually shaking the very foundations of the traditional working and middle classes; it is now facing its new subject, an emergent social body that does not yet have a name. Socialized labor, now almost a thing of the past—since it has almost fully dematerialized—made one thing possible: social equity. With its powerful local and international bodies, this historical middle class helped keep things in balance. The workplace was the site of social organization. As this consensual space is being phased out of our social balances, so is the possibility of checks and balances.

The new global ‘middle class’ does not need the nation-state (or welfare state) as a buffer to defend itself. It shares roughly the same characteristics globally: a common language of transaction, English, and a particular set of mutual codes that override peculiarities of difference. Difference is no longer organic: It is selected, exchanged, and consumed.

“Many of us—members of the diminishing middle classes on the periphery—will continue complaining about the exclusion of our art from art history. The complaint is based on both our acceptance of the parameters that determine art history and our trust that we are part of the hegemonic, horizontal circulation mechanism. Our real support group, the one that nourishes our art, the site-specific middle class, is ceasing to exist—and so are we as its expressive tool. The traditional path to success was to make it big within the local middle class to then be catapulted into the international market. It was a process hampered by the dynamics of imperialism and chauvinism, but success was not completely out of the question. If, however, our home-class disappears, things are bound to become even worse.”1

The intellectual appendage of the new social body is conversant in contemporary thought, using thought not for critique but for empowerment or revisionism. This intellectual acts as a cultural translator and is systematically ushered into the centers (places of exchange and concentrated capital) to speak on behalf of his cultural space, effectively representing it. Some common meeting grounds are the biennials: Havana, Johannesburg, Kwangju, Sâo Paulo, and Istanbul. The proliferation and entrenchment of periodic exhibitions, lodged into cultural phenomena in recent years, have to do with the three-tiered structure that forms a segment of the new contemporary art order, where the biennial exists as the venue, the neoconceptual installation as the main mode, and the curator as a kind of privileged cultural translator.

This new global circuit is no longer superseded by the traditional order of the contemporary art institution but works in relative harmony with it. While they may belong to two leagues (major and minor), crossovers are possible due to relative porosity. Generally, the saga of a ‘biennial artist’ is to travel from one international exhibition to another without gallery support, survive on residencies, and participate in ghettoized multicultural-agenda shows. A cross-referencing of the biennial artists and curators would disclose a rather tight circuit. This could be regarded as a global ghetto for the marginal figure, who is simultaneously empowered by his marginalization through a certain kind of inclusivity but still on the edges of the grand histories of contemporary art.

Although the actual fate of geographically and meta-geographically underprivileged Third Worlds is mutual, the only communication between them is forms of cultural expression delivered through media. So—as has been pointed out many times before—although the favelas in Rio de Janeiro may strike similarities with the slums of Cairo or with some neighborhoods in the South Bronx/these nuclei are not linked by invisible wires that socialize and empower them. Their experiences are filtered through television, and their representations are already mediatized through the same channels for international legibility. These cultural situations are not where most contemporary art comes from but where much contemporary art is derived from.

What is the logic of the neoconceptual installation art coming from the peripheries? The implicit argument, which seemed to justify the move away from painting, was that the art of painting was a Western mode rooted deeply in European traditions, history, and culture (and it was); as such, it could not be indulged in unless it parodied European foundations and traditions. This positioning made the ‘Magicians of the Earth’ a breakthrough exhibition. It proposed installation as an authentic alternative to the tradition of painting. When painting appeared in the show, it either ran against the grain of European tradition or derived from other image-making activities. The exhibition declined authenticity to practicing artists of the periphery by refusing even to consider them. As the title implied, the magicians came from the earth, not from the world, and the ‘Other’ was delegated a nonurban position.

Since ‘Magicians,’ we have seen abundant contemporary work, hailing from the geographical and meta-geographical peripheries under the broad rubric of ‘neo-conceptual installation’. But unlike installation art at its inceptions, the recent work embraces the institutional space either without critique or treats it as a generalized cultural manifestation; although it is evident this posture also satisfies a set of expectations that are already shared among the institution, the artist, the curator, and to an extent the public. In denying the classical tradition, the peripheral culture at certain times could lock itself into the unavoidable position of inventing an origin like the one proposed in ‘Magicians’. The neoconceptual installation does not signify ‘an authentic alternative’ of a representational space outside the tradition of painting, as that show had so erroneously tried to actualize. It cannot have anything to do with magic, ritual, or other such specific local traditions, as such traditions are not categorically continuous with contemporary art. The transfer from ritual to contemporary art is often a vampirism of local culture; at times, it can even destroy local culture by disturbing the ritualistic space because this space does not need the kind of self-consciousness that contemporary art must.

The linkage to ritual represents nothing more than a willful ignorance of the histories of contemporary art and a need to append one’s work or co-opted cultural history to graft it onto an international format and effectively appropriate it. All is possible with a bit of ethnonarcissism. What, then, is the status of this new essentialism, this leap of faith, and the radicalized problem between the site of borrowing and the space of delivery?

It may well be that globalization is irrevocable and attests to a reciprocity between the local’s projection of what the center desires and the center’s projection of what the local should desire. Anyhow, the presence of the local in the work hardly makes the work local. We have moved from a period early in the century when the ‘local’ aspect of a work was a kind of collage over a received format to a period when the local contenting activity seems organic.

A well-known argument that justified the move away from European historical tradition, not merely in making images but also as an institutionalized vehicle, was that it could not be applied to the periphery. A similar argument could also inform European and American conceptualism. Although the shift could have been synchronous at the centers and in some peripheries, the reasons for the shift were not comparable. The shift in Europe and North America was very much within the tradition of painting and Western art history, dating back to the critical avant-garde. The reaction to painting, however, on the part of the peripheral, was also a reaction not to that tradition per se but more to peripheral heritages.

One aspect of the reaction to the peripheral heritage was due to its evolvement into an ‘international style’ passed on to each new generation by the ever-Westernising elites through numerous Beaux-Arts and Bauhaus traditions that were often supported by ascriptive, enlightened, progress-oriented elites and their institutions. Instead of providing possibilities, this institutional structure dictated restricted dogmas of the centers. The general rule was to play a catch-up game, creating highly restrained, surface-oriented versions of ‘modern art.’ The peripheral producer would enter into an elitist dialogue with the immediate viewer and a humiliating relation to the penultimate goal, a place in the Western tradition, to produce highly restrained, formalized work that often shied away from articulating the world. Hence, the lame abstractions were predominant, including painting traditions in the former Soviet Union and its satellite systems or figure-fearing North African abstraction traditions. It should be evident that ‘official’ art was not heroic, propagandist art; to the contrary, ‘propaganda art’ would merely provide the symbolic limit to which the local modern could deviate.

The removal from the public space (embedded in the categorical silence of learned abstraction) could not simply be seen as a civic denial to participate in the public space; no, it was also about giving tacit support to the status quo. It was, thus, not in the slightest sense, transgressive. Early in the century, a given work’s local ‘aspect’ would be a collage over a modern form. Since modern art, in its very inception, indulged in the traditions of the Other as a way out of the weight of its own histories, it allowed the peripheral to claim that in returning to their very own, often ‘national’ heritage to collage the local archeology over an adopted structure, they were reclaiming their traditions. However, it would be nothing other than an archeological gesture. In that, the periphery robbed itself of possibilities and not the Center’s desire for the Other’s traditions.

Protected by borders that empowered them, the locals were self-appointed agents of Europe and later America, and as modern copyists of the periphery, they had no place to go. As compensation, their works adorned the walls of provincial museums, providing all too common localized genealogies, interesting only for reasons of creative misunderstanding, sociology, and possibly as insular history.

This is precisely what made the ‘Magicians of the Earth’ a watershed exhibition because it attempted to bypass the local authorities of the peripheries. The peripheral art institutions were too tainted and corrupted by a parasitic relationship to the ‘West’ and, as such, could not support authentic possibilities for the creation of genuine work, let alone present it. That the premise was well-intended did not guarantee in any way that the ‘authentic’ could be discovered. This problem aside, and how it effectively denied the possibility of urbanity’s presence to the peripheral and opted for urban artists of the West vs. non-urban artists of the East, the exhibition set off a global shift, a radical outburst of neoconceptual installation work. The shows failed twice, miserably: first by bringing organic cultural production into the museum space and its tradition, and second by juxtaposing the Western artist with the magician. The precise break between the early installation work that came out individually and intermittently in the periphery and the wholesale shift to installation practice globally, especially after 1989, has not yet been appropriately addressed. The recent practice is a global virus as far-reaching and leveling as the cosmopolitan internationalism that preceded it.

Essentially, conceptualism is as Western as the tradition of painting, while the reference here is to a West that has already lost its authorship—to claim a categorical distinction between the two, either in the center or in the periphery, is pure formalism. While there may be a discussion about the possibilities and different approaches to producing art in different places, physically or theoretically, the distinction between the painting and neoconceptual practice is an artificial one sustained by a new power structure that has little to do with issues intrinsic to work. Likewise, local content is not a sufficient criterion for assessing any work, and as such, reducing a work to a concrete reality has no relevance. Local contenting’ (if we borrow a term from automobile parlance: dressing over a received form) can only imply a fetishized difference, not unlike the difference between a Honda Civic and a Toyota Camry, when the truth is that the auto industry has been a remarkably boring one, never abandoning the same four wheels for the entire century.

The sincerity of the argument of the late ’80s towards a decentralized international art institution has been reduced to the proliferation of complacent power ghettos. The late ’80s were globally a moment when hybrid identities were still being negotiated and readers of contemporary thought could produce authentic texts and answers in their ‘home’ positions. Many globally accredited thinkers made a vital discursive sphere possible. Now, authentic arguments of hybrid cultural forms and nongravitational possibilities are reduced to the repartitioning between emergent power bases.

The radical political shifts in the ’80s the end of the military dictatorships—or their replacement by politically and economically efficient liberal economies—created (as it was also created by) the global maturation of the intellectuals who were conversant in interdisciplinary thought. They used the French philosophy not for critique but towards empowerment, precisely because they had initially benefited from their sheltered lives under dictatorships and from the textual critique that ensured perversely and made possible critical interpretations that did not have to be inserted into the political structures that made the thought possible. They, in short, became the characteristic subjects of the 20th century.

The orbital structure of the provincial modernization ensured a local space and made it possible to survive. It could be said that the provinces had little if anything to offer the Center throughout most of the century except for a few instances that are now being granted processually, but the current flow of the peripheral to the center and the center’s desire to acknowledge it has to be kept separate and away from the opportunistic revisionisms. Shit happens everywhere, but the ‘center’ does not merely consume or validate it. It still provides a critical ground for assessment.

- Luis Camnitzer, ‘Cultural Identities, Before and After the Exit of Bureau Communism,’ The Hybrid State, Exit Art, 1991. ↩︎